9. William Prinsep in Canton, caught with his hand in the tea bucket

Prinsep's memoir of his voyage to Canton is a tale of espionage, smuggling & culture shock; a narrow escape from the Chinese police; and a tense meeting with his painting master George Chinnery.

It was the 14th July 1838, and the Lord Hungerford was sailing through the night, driven by the hot monsoon winds up the Bay of Bengal, still two weeks from Calcutta. The two misses Dick lay fast asleep in their cabin, dreaming of family soon to be discovered for the very first time: brothers, sisters, in-laws, cousins, a mother and father last hugged tearfully 13 years and a lifetime ago.

On that same night in Calcutta a small group of figures huddled on a ghat by the Hooghly River. It was 4am: William Prinsep complained of a splitting headache, exhausted from his preparations for a long voyage. He and his wife Mary — she was one of Eliza’s many cousins in the City — waited anxiously with their two daughters for a tender to row across to the Bolton, an East Indiaman lying at anchor a chain’s distance across the water, readying for a steam tug and a tow down to Sagar Island. There were 75 miles of twisting swift running water before the river opened out into the sea, a dangerous journey for a large sailing ship made safe by the vessels of the Steam Tug Association; this navigational innovation was supplied by the enterprise of Carr Tagore & Co, the agency and holding company in which William was a partner. He was on leave of absence, making a long-promised visit to his brother Charles at his nutmeg plantation on Mount Sophia, a green hill overlooking the port city of Singapore. Today this is the site of the Presidential Palace, called the Istana1. The voyage would take 3-4 weeks, beating against those same monsoon winds, sailing south for Java.

Nine weeks after their arrival in Singapore the vacation was curtailed. In late September the opium clipper Water Witch sailed into the mouth of the Singapore river with despatches: at the urging of her commander, Captain Reynell, William abandoned his family to race to Canton (Guangzhou). He recorded the eventful journey in his diary and later in his memoirs, written 30 or so years later.

The Water Witch was the pride of Carr Tagore’s fleet, described in William’s memoir as, ‘a charming yacht-like vessel of about 360 tons rigged especially for fast sailing & armed with 5 guns as defence against the pirates of the China Seas’.2 The clipper was one of the fastest ships then afloat, its speed designed to evade pirates, yes, but also Chinese customs police, and to be the first of the agency ships to unload its cargo of opium onto the local smuggling boats and so obtain the best price from the cohongs, the cabal of Chinese merchants on the Canton quayside. Opium smuggling was not the main business of Carr Tagore but a profitable sideline — a thrilling or risky gamble, depending on which partner you were talking to. On this voyage, however, Water Witch also carried secret despatches from Prinsep’s other partner, William Carr. He had recently arrived in Calcutta from London with sensitive information on European silk prices. Prinsep’s task was to take these on to Dent and Co., the partners’ agent in Canton.3 There was, however, yet another motive for William Prinsep’s trip: he wished to indulge a new-found curiosity in growing and processing tea, a mission in which he enjoyed some success, but which very nearly cost him his liberty, if not his life.

Water Witch’s arrival on the Chinese coast two weeks later was picturesque:

‘We anchored at 8pm in a quiet bay entirely surrounded by little mountains, the shelter so perfect that the sea was like glass. As soon as it was dark we were surrounded apparently by a multitude of dancing will of the wisps. They are small fishing boats to which they affix a light at each end, and then dance them up & down to attract the fish which they catch in great numbers, — this process being accompanied by the beating of small tom toms — in a beautiful still night — made it quite a scene in Fairyland’.4

‘At the earliest day light a small sampan boat was hired to take me at once through a back passage to Hong Kong as I was to carry the Firm’s dispatches to Dent’s house with all possible secrecy and haste’.

The perils of arrival in the Pearl River delta were twofold: first, being sighted by the ships of rival European trading houses off Hong Kong island; second, running up the river in the dark below the Bogue Forts where the channel narrows between islands, avoiding police stations and any challenge or close examination of a fanqui with no permit and criminal intent.5 Unbeknown to William, the presence of the Water Witch was reported to the European factories in Canton well before his arrival and his secret mission was blown; and yet he still had to make his way past the Chinese forts in the Pearl River on a bitterly cold night, huddled with no blanket in the stinking bilge of a local boat, ‘truly a fast one and remarkably well handled … her two large mat sails laid her gunwhale under most of the way’.

Having transferred on and off two further ships, navigated past Whampoa and arrived in a yawl at the the quayside of the foreign factories, Prinsep was confounded by culture shock:

‘What strange figures! what novelty! What entire and complete difference in the form & feature of everything - even to the pigs and dogs, the only animals met with. The very colour of the atmosphere seemed to be different from that of any part of the world I had ever seen, & each figure which passed was a picture I should like to jot down. But it was everywhere crunch & noise & the loud monosyllabic language appeared to be jerked out of their mouths with an effort.’

Prinsep was fascinated by the Chinese, impressed, sometimes appalled by the delicacies eaten, apparently scrupulous in his own conduct and the honesty of his observations: tales of haggling in shops and being refused the better items because, as a European, he was not considered able either to afford or appreciate them; sketching shopkeepers and their customers on Fan Street and Lantern Street; buying drawings of an opium smoker from Lum Qua, a fellow painter who had also taken lessons from George Chinnery; watching the wedding procession of the daughter of Minqua, the merchant of the French Hong; attending performances in the theatre and opera at the great Sing Song houses; visits to temples and Joss houses; surviving an extravagant and challenging dinner at Minqua’s house with Captain Laplace, leader of a French scientific expedition, recently arrived from Macao.

Always in the background, occasionally evident in street altercations, there was a tension in the City caused by the growing opposition to opium smuggling from Chinese officials. According to Prinsep, there were ‘disagreeable influences going on between the Viceroy & our plenipotentiary.6 The English Hong flag is struck & some trouble is expected’. The conflict was a matter of occasional debate between Europeans. In Singapore, two months earlier, William and friends had become involved in a ‘tremendous argument’ with Daniel Wilson, the Bishop of Calcutta, on ‘the great problem still unsolved of: are we to be excused for supporting the opium trade?’ William is silent as to his viewpoint or the outcome of the argument. Evidently, the opium smugglers were aware of the opprobrium their activities attracted: they did not exist in some kind of 19th Century moral vacuum. Within the 13 factories, a Mr King proposed getting up a memorial against the opium trade, creating a dilemma expressed by William as: ‘The Christian view cannot be denied, but how to apply it? … who among the merchants will carry up to the Viceroy their signatures, acknowledging their complicity in breaking their smuggling laws?’. The answer was clear: not Jardine nor Matheson nor Dent. His greater concern was the likelihood of further restrictions on a trade in which Carr-Tagore had too much capital ‘afloat’ (literally and metaphorically), a ‘gambling trade in which our native partner [Dwarkanath Tagore] found more pleasure … than in many of our other operations’.

Prinsep, as the soon-to-be general manager of the Bengal Tea Association, was in any case much less interested in opium than in tea: how it was cultivated, how it was processed and prepared for sale, how it was consumed. In China, ‘a visitor who desires to confer with the master is expected to sit & partake of a cup of boiling hot exquisitely good tea, of course without sugar and milk which are barbarous additions’.7 William’s industrial espionage took him to an establishment of makers of “Young Hyson” tea: a variety today described as warm, sunny and spring-like.8

‘We were received hospitably in their garden with sweetmeats, fruit & tea. Their process was simple. The old tea much of which looked like re-made or lie tea was placed in small quantities at a time in shallow iron pans heated over a range of stones … A small portion of powdered Prussian Blue was thrown in by an overseer & then a coolie at each pan kept the tea constantly in motion by his hand tossing it up in the air so as not to be too much heated but sufficient to receive in this sweating process a facing or bloom of the exact character of the usual green tea, but upon my examining & smelling it, the mandarin with a smile told me “is for America market”. It is in fact a lie [tea] throughout & will be sufficiently profitable until the buyers generally find it out, but I have no doubt that in the large exportation of 100 millions of pounds a very considerable portion of the tea, both green & black, is surreptitiously introduced tho’ generally detected by the tasters in Mincing Lane.’9

And so William Prinsep may have done the world a favour by identifying one of the means by which quality teas were adulterated with base ingredients. Gypsum, which makes green tea greener, is a broad spectrum poison that acts on the nervous system; Prussian Blue, used to fake green tea from lie tea, is not toxic to humans, despite containing cyanides; but the black lead used to adulterate black tea certainly is. Such investigations are unlikely to have brought Prinsep to the attention of the Viceroy, but the care he recalls in preparing his luggage for departure (every package had to be ‘chopped before it can be removed, ie. it must have the Hong stamp or certificate of duty paid.’) suggests that contraband was involved. William admits only to being caught, apparently en route to Macau, by customs officials ‘with his hand in the tea bucket’, and only the personal intervention of the British plenipotentiary, Captain Charles Elliot, ‘who had removed his evidence during the quarrel with the Viceroy to this place.’ Elliot would be a principle actor in and initiator of the conflict that escalated into all-out war just nine months later. He had saved Prinsep from imprisonment or worse, because an act that breached the regulations governing the Canton system was potentially a capital offence. William is silent again as to how the quarrel was resolved or what exactly he took from the “tea bucket”, but it is likely to have been tea seeds or saplings to experiment upon in the tea gardens of Assam, and it is likely too that Water Witch had brought not just the latest London silk prices to Canton, but also news of the Indian Government’s intention to offer up its experimental Assam tea gardens to private business, a nugget of inside information that Carr Tagore had received via a friend who was in the know, George Gordon.

Why was William’s tea smuggling such a crime? China had an effective global monopoly of the knowledge and varieties needed to manufacture quality tea. Britain was addicted to tea, and in 1840 British merchants collectively purchased 35 million lbs of the stuff in Canton, paying in silver with a value of around £4.7m. When sold in London that tea generated a gross profit of over 100% and the resulting duties contributed 10% of the contents of the British exchequer. Exports of tea to Britain accounted for 80% of the value of the Canton market and, at today’s prices, as a share of GDP were worth the equivalent £74 billion. This provided a source of bullion that the Chinese empire would not easily go without, and foreigners were forbidden from entering tea growing districts where they might steal both the knowledge and the plants. Between 1848 and 1852, the plantsman Robert Fortune stole both, and on behalf of the Royal Horticultural Society smuggled out of China 20,000 tea plants, eight tea farmers and quantities of tea manufacturing equipment. William Prinsep’s escapade was a precursor to many others, with the result that the monopoly was torn down garden by garden over the next 70 years, and by 1928 India and Ceylon had a combined 56% share of global tea exports. The British had won the tea war.

Opium, that toxic colonial crop, poisoning the lives of its users and the livelihoods of its farmer producers, was at an earlier time a vital component of the triangular trade between England, India and China involving opium, silver and tea because it provided equilibrium to the balance of trade; now it provided a huge surplus. In 1796 Henry Dundas (yes he, the patron of Dr William Dick) argued in the British parliament that Bengal — and by extension England — would be drained of silver to pay for tea and that only opium exports could stem the flow; this was an assertion that ignored the fact that Britain recorded an overall positive trade balance with China in the years 1792-95 — excluding opium sales — and that this was largely achieved through sales of Indian cotton. There is more than a hint that Dundas was seeking to justify continuing an immensely profitable criminal enterprise by citing economic necessity. To ascertain the truth we can deploy simple arithmetic: sales of opium had risen to 40,000 chests per annum in 1840, with a quayside value of approximately £17.4m; that is 3.7x the quantity needed in the same year to pay for total tea imports of £4.7m; this leads inevitably to the powerful conclusion that the principal purpose of the opium trade was no longer merely to prevent the drain of silver from England caused by tea, but to fill the pockets of the Indian Government and thence the British Government. The British exchequer took 10% of East India Company revenues, of which the profits from Bihar and Malwa opium made up a significant portion; the opium business filled the pockets of the English and Scottish traffickers, their banks and investments in Far Eastern colonies; and, via private trade and the clippings from bengal bonds, the opium trade contributed vast sums to private capital invested in British manufacturing and infrastructure. No wonder that Britain fought two wars to preserve this trade.10

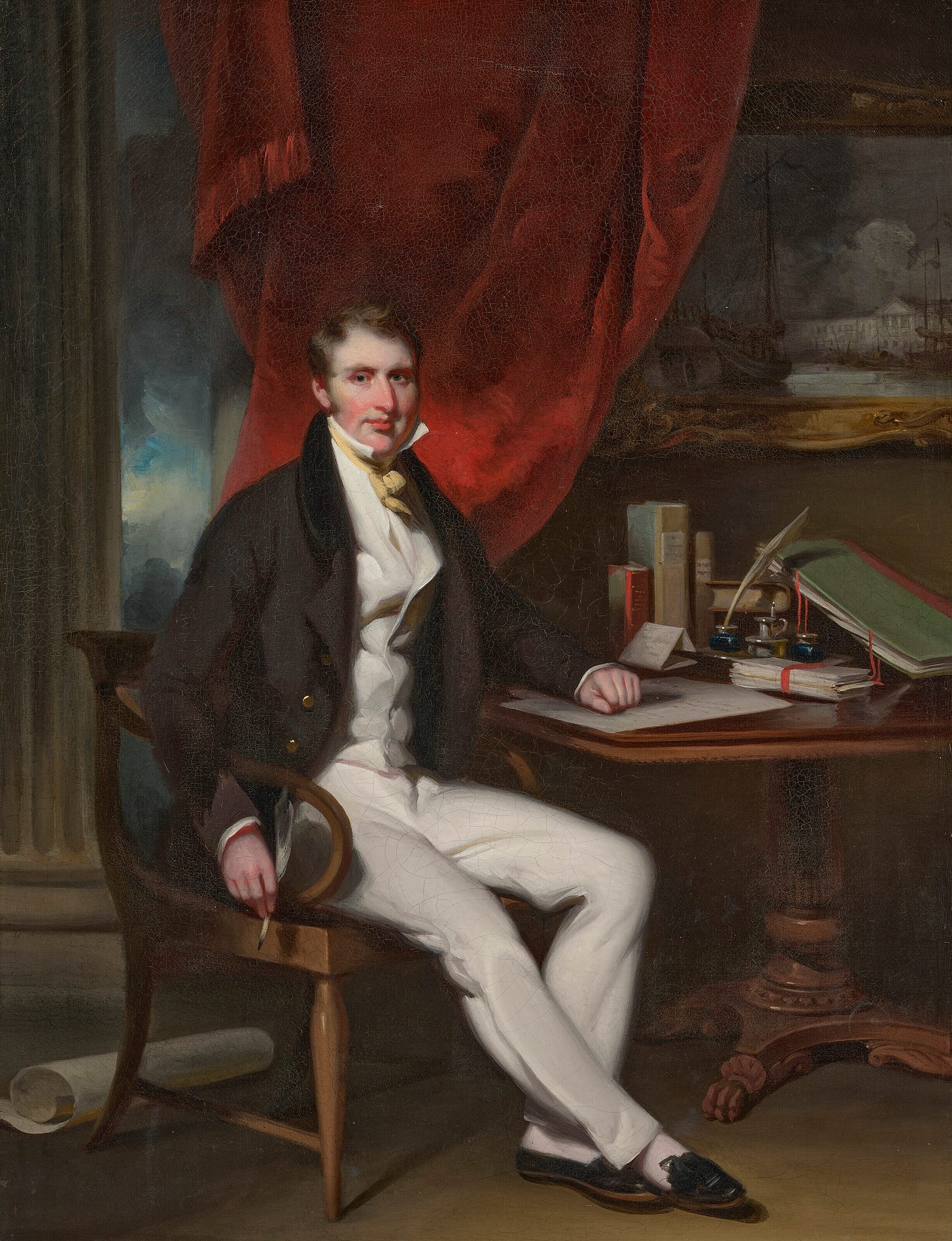

In 1838 there were as yet only intimations of the Chinese crack-down that would begin in the Spring of the following year and soon escalate into the First Opium War. Prinsep, writing in hindsight, said that from Charles Elliot, “not a hint [was] given about any expected quarrel with the Chinese Govt.”. In Macao, where William had arrived after his brush with Chinese officialdom, he might have learned more from the opium merchant William Jardine, whom he found at George Chinnery’s studio in Macao sitting for a portrait. “The Iron-headed Old Rat”, as he was called by the Chinese, “the sly and cunning ring-leader of the opium smugglers”, as he was called by the new Viceroy not yet in post, Lin Zexu, was on the first leg of his return home from Canton to England, ostensibly to retire, but in reality armed with an introduction from Captain Elliot to Lord Palmerston, to lobby the British Prime Minster to wage war on China according to a blueprint provided by Jardine to guarantee defeat of the Emperor’s forces and enable the expansion of the opium trade. William Prinsep, though, was more interested in the quality of Chinnery’s painting of Jardine, not at all in Jardine’s view on relations with the Middle Kingdom.

Chinnery and Prinsep, reunited after 18 years apart, found themselves at loggerheads, their meetings fraught. They squabbled. There was history. Having left London for Calcutta to escape his creditors in 1802, Chinnery had left Calcutta for Macao to escape a new condescendence of creditors in 1825: a pattern was emerging. Palmer & Co (William’s former partnership) had advanced substantial sums to Chinnery and after he absconded, William Prinsep — with his artist’s eye — had discovered several sketchbooks ‘of considerable value, made over [by Chinnery] to a French merchant surreptitiously, when indebted to us so largely. I had of course impounded them & finding him not inclined to redeem them I sold them as payment of our claim’. Chinnery gossiped in Macao that Prinsep had stolen his sketchbooks and vilified him to all and sundry as a robber and extortionist. Prinsep responded: ‘I found that none of the residents had given credence to his little charges, but I took care they should know the truth & found that Chinnery’s character was well known before he went there. He was only tolerated for his paintings’.

An elaborate public reconciliation was designed by Chinnery to salvage some of his pride. Prinsep, the merchant trader, paints a sorry picture of the artist: ‘He was to be seated in a room at Inglis’ with his back to the door. I was to be introduced by two friends round to his front when he would rise & receive my proffered hand without any reference to the past. This was carried out to the letter amidst the laughter of all present who were highly amused at the same, after all his vapouring & abuse of me.’

Of Jardine’s portrait and other new works, Prinsep was unflattering, ‘… though his pencil was as true for design as ever, his painting had certainly gone off. His former faults of exaggerated lights & shades were more prominent than ever’. Prinsep was however fulsome in his admiration of Chinnery’s China paper sketchbooks, with the observation that his trick would never pass from him. Chinnery said, “Do you like it? - accept the book as a peace offering from George Chinnery’” And of course Prinsep did: ‘I have the book still & by artists it is considered a most valuable acquisition - it is of Chinese subjects entirely.’

Their parting was however soured by another small lie from Chinnery: and ‘so ended my communications with this extraordinary man whose talent was of the highest class & who if he had but been honest might in Europe have made a great name for himself.’

William Prinsep returned to Calcutta on the Ariel, another of Tagore’s opium Clippers, and he arrived safe and sound in the Hooghly River on December 15th, after a slow run from Singapore. He had mended his breach with George Chinnery, but not changed his opinion for the better; he had made dozens of sketches, many of which were later turned into water colours and oils; he had met the French artist Auguste Borget, who would became a close friend in Calcutta; and he would soon be hearing of Abercromby Dick’s breach with Dwarkanath Tagore from his partner, William Carr, who had joined the ship downstream from Calcutta. William’s ‘secret mission’ was a good excuse for an exotic voyage but otherwise a goose chase or canard; and yet Prinsep had learned some hard and useful lessons about tea, which were no doubt of value in the formation two months later of the Bengal Tea Association, a joint stock company, founded in February 1839 by Carr Tagore and Co., it’s General Manager William Prinsep.

You’ve just read the last of four chapters on Dwarkanath Tagore, William Prinsep and the Bengal Renaissance. If you missed the others, start with the first, here:

6. The machine in the garden

Government House in Madras (Chennai) was built in around 1750 and enlarged in 1778 by Sir Thomas Rumbold, ‘a notorious nabob’, and then again in 1801 by Lord Edward Clive with the engineer John Goldingham. Their contribution was a Tuscan-Doric banqueting hall to commemorate the victory over Tipu Sultan in 1799. Fortunately, the new addition was erected apart from the main building, for it was ‘in vile taste’, as described with commendable restraint by Reginald Heber, the Bishop of Calcutta.

Also onboard the Bolton were two other members of the Auriol-Prinsep families: Mrs Adeline Maria de l’Etang Pattle and Captain Alexander Dashwood, William’s cousin. Mrs Pattle was the mother of Sara, wife of William’s brother Thoby, and Julia Margaret Cameron, the pioneer photographer who had recently married Charles Hay Cameron in Calcutta; he was a Benthamite and Macaulay’s advisor on the Indian Law Commission.

WP memoir Vol.3 p54

Lancelot Dent was Carr Tagore’s agent in Canton, not to be confused with Wilkinson Dent, which was the mistake William had made: ‘I was taken quite aback on finding that W Dent was not my friend but a perfect stranger. He saw at once my embarrassment & said smiling “Oh it is you then that have arrived in the Water Witch.” - My secret expedition was there already blown up.

William Prinsep Memoir Vol 3 p58

Conventionally this is translated as ‘foreign devil’

Captain Charles Elliot, the British Inspector of Trade and Plenipotentiary

WP Memoir Vol 3 p69

Hyson (hi-tshun) refers to the Chinese green tea processed as twisted leaves that are long and thin that unfurl slowly to offer its fragrant astringent green taste. Hyson tea has been defined as warm, sunny and spring-like, reflecting both the color and the season in which Hyson is harvested. The better quality "young Hyson" is harvested "before the rains" and has a pungent, full-bodied taste that produces a golden liquor with an edge of sweet character in the cup. Not all Hysons are good grades, and many tea vendors give the name of Hyson to those green teas which are light and inferior leaves that remain after the better quality leaves are sifted out (usually by machine.

Mincing Lane was the principal tea exchange in London. Lie tea was made with toxic ingredients, prussian blue, gypsum or puverised black lead. In 1861, a Virginia newspaper reported on a study published by the journal, The Lancet, which looked at 24 samples of black tea and 24 more of green. Though they found that all of the black tea was “genuine,” the bad news for green tea drinkers was that all of it was adulterated. They defined lie tea a little differently, calling it “a leaf which resembles the tea leaf closely, and is sent to this country from China in vast quantities, to be employed in adulterations here.” https://blog.englishteastore.com/2014/05/16/the-truth-about-lie-tea/

The total value of the British trade in Bengal opium to China in the years 1782 to 1859 was according to J. F. Richards, £126.4m, resulting in a net profit £88.5m at the 70% margin estimated by contemporary commentators (see Chaudhuri), being £425bn in 2022 comparable economic share. Direct sales of Bihar opium and taxes charged on Malwa opium made a significant contribution to the 10% of company profits taken by the British Government to fund its military spending, amongst other outgoings. The aggregate revenue achieved in 1851-59 was £45m, equivalent to a capital investment today of £156bn. In the mid 19th Century this was enough to fund between one quarter and one half the capital invested in British railways. Opium primed the second phase of the industrial revolution. See https://eaho.substack.com/p/the-importance-of-a-free-lunch-in