6. The machine in the garden

A visit to Madras, 1839; the glory of the garden house; dinner with Lord Elphinstone; the beautiful Jennings sisters; Macaulay's comical code; MacNaghten's last cry; the talented William Prinsep.

Government House in Madras (Chennai) was built in around 1750 and enlarged in 1778 by Sir Thomas Rumbold, ‘a notorious nabob’, and then again in 1801 by Lord Edward Clive with the engineer John Goldingham.1 Their contribution was a Tuscan-Doric banqueting hall to commemorate the victory over Tipu Sultan in 1799. Fortunately, the new addition was erected apart from the main building, for it was ‘in vile taste’, as described with commendable restraint by Reginald Heber, the Bishop of Calcutta.2 Regrettably, the banqueting hall is the only part that remains today.

Government House is or rather was a beguiling mix of Indo-Saracenic and classical European architecture. One of the last visitors to see the house before its demolition in 2008 described the interior: “The flooring boasted of some of the highest quality marble. The first floor central hall had fine plaster work and the hall fronting the verandah had a beautiful false ceiling held up in a framework of rosewood that shone as though it had been put up yesterday. The ornamental pillars that rose up to the ceiling were made of rosewood and carried monograms of officials and rulers of the past. At least 10 doorways were made in the finest Dravidian style, each one of them at least 12 ft in height. The ceilings were of the Madras roof type with Burma teak rafters. The staircases had wooden bannisters with some outstanding wrought-iron work holding them up. All of these were instances of native craftsmanship, none of which survive today …. the work of thousands of Indian masons, woodcarvers and other artisans”.3

The house and its setting are described in Palaces of the Raj, by Mark Bence-Jones: ‘As the most traditional city of British India, it was fitting that Madras should have possessed the most traditional of Government Houses: the finest surviving example of a “garden house”, the country residence of a rich or important European, or Indian of European tastes, in the eighteenth century.’4 Julia Maitland gives a contemporary account of a ball at Government House in the 1830s: “The Nawab entered with a grand suwarree of a hundred guards, and a hundred lanterns all in one line, and appeared like a man of penetration. The English danced together pleasantly after their fashion, shaking each other’s hands, and then proceeded to make their supper, when the respectable natives all retired”.5

The house was photographed by Eliza Ogilvy’s grandson in 1917 when, in accord with the family tradition that every career path touches at Madras, he was Military Secretary to the Governor, Lord Pentland. His pictures show an interior of doric columns, marble floors, antique canons, huge teak rafters carrying the very same rosewood ceiling, full length portraits of long-gone ladies, and a telegraph room with candlestick telephones, nests of plaited woven wiring, a fat London Post Office directory dated 1916, a pigeon hole labelled ‘His Excellency’ and a framed photograph of Lady Pentland flanked by two carved wooden figures representing Sepoys. This is the room in which the 19th Century raj — self-willed and distantly autonomous — meets the 20th, directly connected and urgently ruled from London.

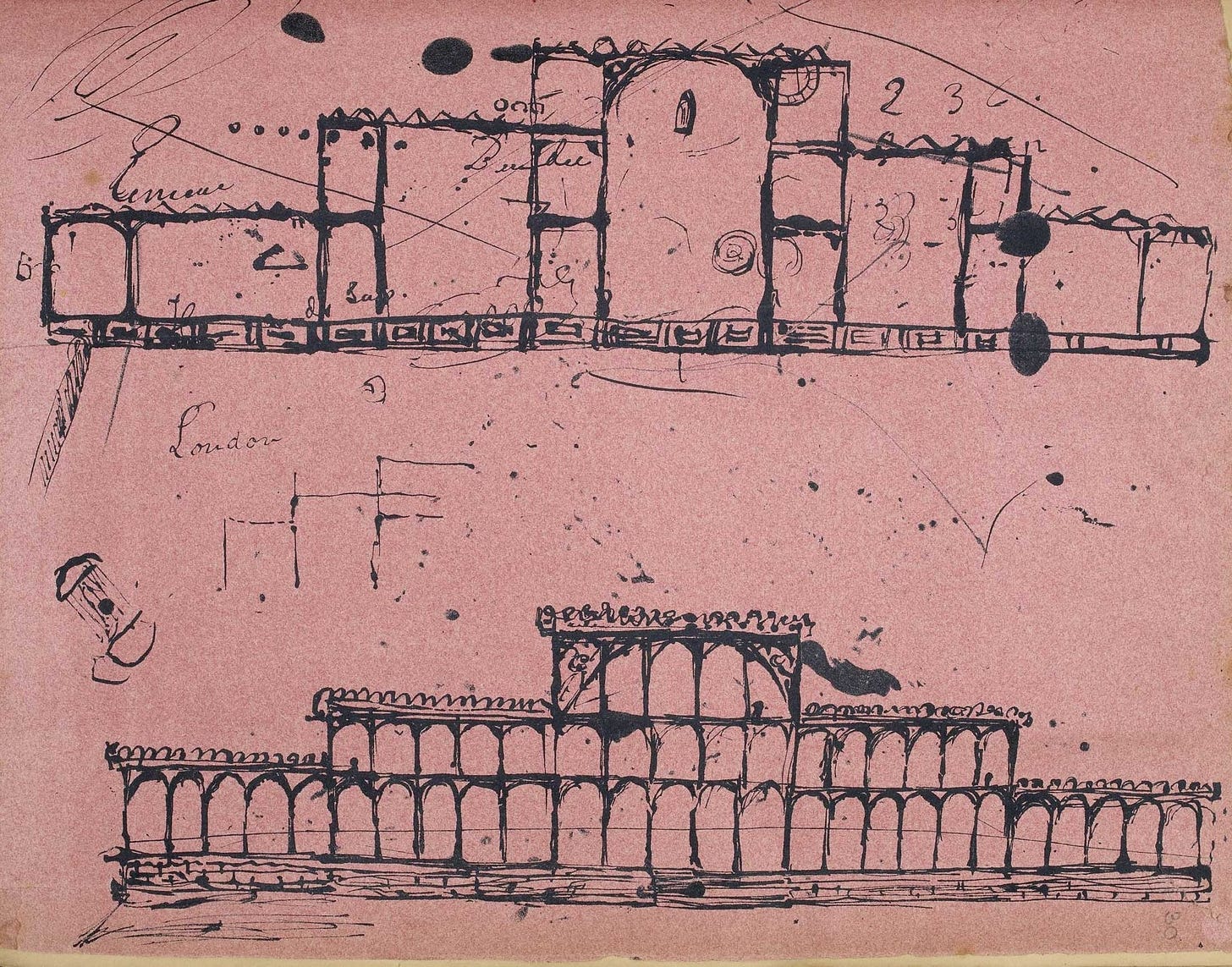

Photographs of the external elevation show a facade of light, rhythmic and regularly spaced doric pilasters and columns, rising over two or three storeys, topped by a flagpole on which a Union flag hangs limp in the heat. Each floor is surrounded on three sides by a deep colonnaded verandah that opens onto the gardens, where antelope graze between palm trees surrounding a wide lake, and thus the house dissolves into the gardens surrounding it: it’s an example of the simple and repetitive classical form that became a model for industrial architecture in Europe in the second half of the 19th Century; its lightness and modularity translate effortlessly from stone into cast iron, and it’s easy to think of Paxton’s initial sketch for the Crystal Palace, for example, or mid-19th Century European market buildings as inspired by the open classical arcades surrounding structures like Government House and then simply turned inside-out.

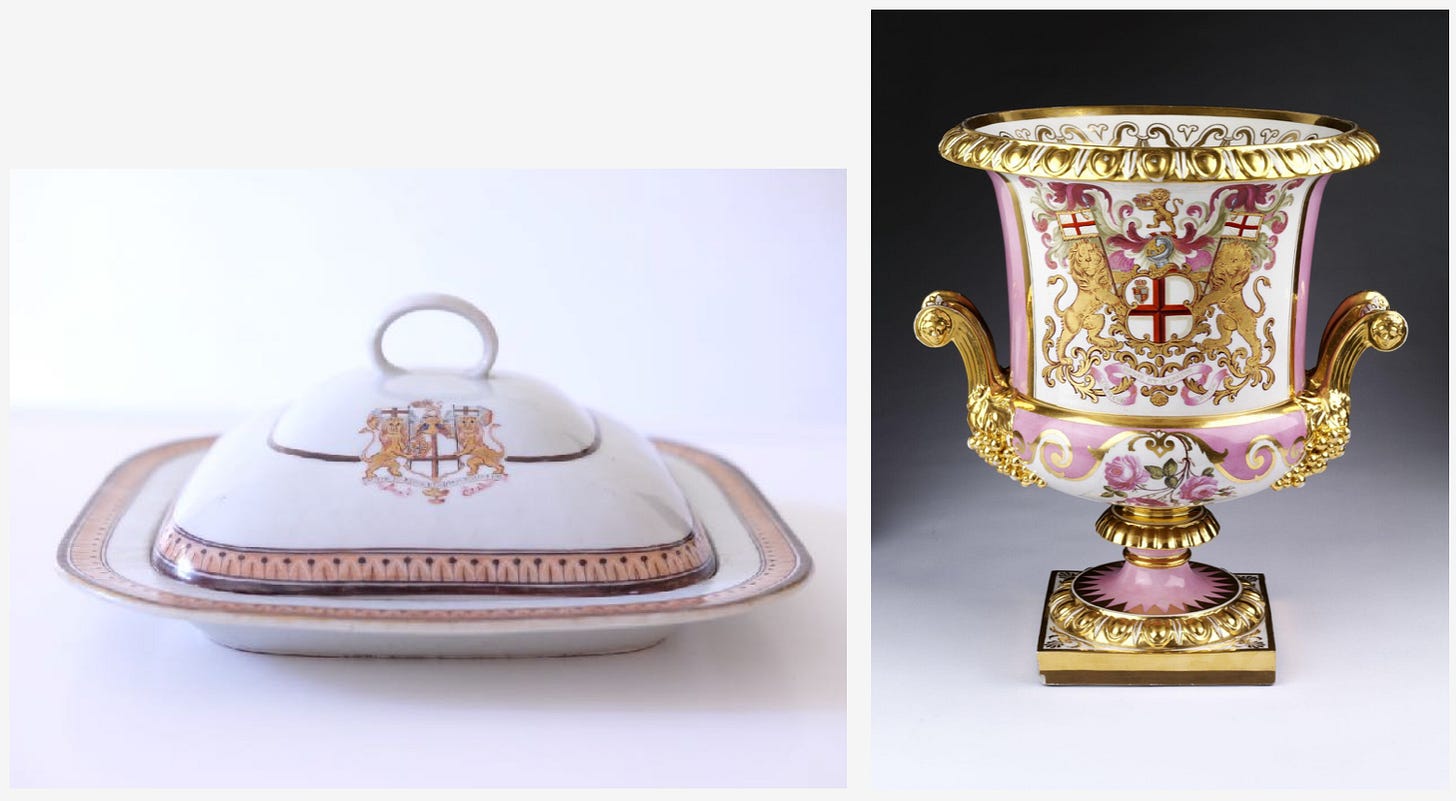

When Eliza, now 17, sailed from Calcutta to visit her uncle in Madras in early 1839, we can suppose with easy confidence that Sir Robert Dick would have introduced her to the Governor of Madras, Sir John Elphinstone, who thereupon became the inspiration for the male lead in her novella, Laura Studlegh. Sir Robert wrote to his brother William in 1839 ‘Lord Elphinstone keeps a capital table, & is very hospitable and we get on well’. Dick rarely dived any deeper. Also, with some certainty, we can assume that she met for the first time her second cousin, Charles May Lushington, secretary of finance to the Government of India and daytime resident of Government House.6 Then, stretching credibility only a tiny bit further, we can presume that she supped in the dining hall with its Dravidian arches looking out to the parkland beyond, eating dinner from a porcelain service made in 1798 in Jingdezhen and decorated in Canton with the arms of the East India Company, loosely painted lions rampant, commissioned by Edward Clive to mark the 200th anniversary of the Company’s founding in 1600. Or, would it have been the newer service? With a crisp and more fashionable design, the crest painted precisely, with a high glaze on a background of shocking pink with gilded highlights, by Barr, Flight & Barr of Worcester in 1830.7 The difference between the two says much about how the Company was changing in both its trade and taste, less interested in Eastern culture, more concerned with imposing European ideas on India and, increasingly, importing European manufactured wares into Asia rather than the other way around.

This replacement of Asian with European was part of the pattern of events and practices that culminated in the great uprising of 1857 and had already begun to reveal itself by the time of Eliza’s visit to India in 1838-41. The cultural war waged by utilitarians and Christians against the Company’s laissez faire attitude to Indian customs, language and religion resulted in an influx of missionaries and codifiers to eradicate sati and thuggism, place hard ceilings on Indian ambitions - Europeans would lead, Indians would follow, in both military and civil occupations - and anglicise the law and education. The number of European planters of indigo, sugar, tobacco and tea multiplied; the ‘Forward Policy’ of lapse and annexation that brought more states and principalities under British control was accelerated under Lords Ellenborough and Dalhousie; and the East India Company’s main source of revenue was no longer trade but tax, often extracted with violence. The destruction of Bengal’s textile industry at the behest of Manchester ‘free traders’ had much reduced exports of Indian calicos and muslins to China and Europe and made India reliant on imported cotton. Opium was not only a vital means of paying for goods from China but by 1839 had reversed a trade deficit into a surplus and a source of unimagined profit. Even China tea became less important as the leaves came to be grown at scale in Assam and Darjeeling, using seedlings and knowledge stolen out of China by the men of the Royal Horticultural Society; and the discovery of the secret of making fine porcelain — first at Meissen, then Venice, Sevres, London, Stoke and Worcester — had made export ware from Canton a less profitable private trade for the Company’s sea captains and a less impressive mark of status for the Governors of Madras.

Eliza’s family members were busily engaged in bringing these changes about, some more enthusiastically than others. In 1838 the Dick family in Bengal was not so numerous as it had been in the early part of the Century when Dr William Dick and all of his sons bar Robert had been there together in the civil service, but it had sent out new branches and lost others, torn off in youth. Alexander, the third of the six brothers, had died in 1805, on board ship a few days before docking at Penang, his father by his side but unable to save him. John’s career ended with his early death in 1825 in Calcutta, marked by Aber’s poem. James died in 1831 in Bareilley, where he was judge and magistrate. William Fleming Dick had retired on his Company annuity to Stanstead Bury House in Hertfordshire, just before Eliza and Charley arrived, but the city was thick with his friends and relations in the Low, Shakespear and Thackeray families. And there was Eliza’s mother’s family, the Wintles: Edmund, the eldest of Louisa’s siblings, was a Major in Madhya Pradesh, south of Rajasthan; Louisa’s sister Charlotte had died in childbirth in 1820 in Mirzapore; her brother Henry died in Dum Dum, Bengal, in 1826 aged 18. Out of this carnage Maria Wintle had survived; in 1828 she had married Frederick Millett in the Judges House in Midnapore, a good match presided over by her brother, the Rev. James Devaynes Wintle (and he died two years later in Barrackpore, aged 31). Frederick Millett was from a Cornish family and at the time a junior merchant. In 1837 he became a member of the Indian Law Commission and deputy to Thomas Babington Macaulay, the MP and reformer, historian and poet, who had set out from London to Calcutta in 1834 determined to accumulate his own ‘competency’. After his return — coincidentally in the Lord Hungerford, in 1838 — he never needed to work again, unless he wished it. Macaulay made his fortune but complained about the privations necessary: “During the last rainy season,—a season, I believe, peculiarly unhealthy,—every member of the Commission, except myself, was wholly incapacitated for exertion … Thus, as the Governor-General has stated, Mr. Millett and myself have, during a considerable time, constituted the whole effective strength of the Commission. Nor has Mr. Millett been able to devote to the business of the Commission his whole undivided attention”.8

Despite such lapses, Macaulay came to rely on Millet while other members of the Commission sickened. He was armed with a two-part brief to codify Indian law, ostensibly so that it was applied equally to all — European or Indian — and to reform Indian education according to utilitarian principles; these were applied by Macaulay with an unwavering conviction in the supremacy of Western thought in general and the English language in particular. In law reform Macaulay failed to produce an agreeable compromise and the new criminal code was not implemented until 22 years later (and then only in partial form). In 1838 the fate of the Black Act, as Section XI of the Legislative Council came to be known, remained undecided; it caused a huge furore in Calcutta in which Eliza’s father, Abercromby Dick, became embroiled. A legal system that treated Indians and Europeans alike was, in the imperial context, an anachronism that baffled Macaulay in 1838 and his successors Sir Courtney Ilbert and Lord Ripon in 1883. In educational reform Macaulay had considerable success, to a degree because he was building on a policy already established by governors such as William Bentinck and by Indian reformers, including Ram Mohun Roy, who may have shared Macaulay's ideas about means (such as using the English language as a vehicle for rational scientific education) but not necessarily about ends, which in Macaulay’s mind were to strengthen British dominion and in Roy’s to encourage Indian equality, enlightenment and self-sufficiency.

The reform movement pitted orientalists against evangelists. The Company’s accommodating and careless way of ruling established in the 17th and 18th Centuries, which it called ‘engraftment’, was to be replaced by the assertive and moralistic determination of the Crown. Language was at the heart of the debate because it was used differently by each side as an instrument of rule. The East India Company and its educational institutions had placed the highest value on being able to communicate with, learn from and coerce its subject peoples (and its many equal or superior partners) in their own languages. Dr William Dick, for example, despaired of his son John’s incompetence, unique within the family: “let him be appointed to some inferior branch of the Service that does not require much talents or knowledge of languages”9; whereas Abercromby Dick was a linguistic adept, graduating from the college at Fort William with First in Hindoostanee (sic.) and Second in Persian. The only student to best him was William Hay MacNaghten, the elder brother of Abercromby’s friend Elliot, who had the advantage of prior study at Fort St George in Madras and achieved First in Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit and Hindoostanee and a Third in Bengalee. This did him no good, other than to elevate his career beyond his political abilities. Having encouraged Lord Auckland into the ‘reckless gamble ‘ and ‘rash move’ that was the First Afghan War, this was an adventure that started well for the invaders and then descended into chaos, as did all subsequent Afghan wars whether British, Russian or American. In 1840 the British first occupied Kabul without difficulty and then with breathtaking complacency sent most of their army home leaving a garrison of just 8000 troops, who were permitted by MacNaghten to bring their families from India to join them. Macnaghten himself “purchased a mansion in Kabul, where he installed his wife, crystal chandeliers, a fine selection of French wines, and hundreds of servants from India, making himself completely at home”.10 Then, as political officer with the expedition, he made the mistake of betraying in writing Aminullah Khan Logari, one of the leaders of the inevitable rebellion against the British that broke out in 1841. The fatal betrayal was made to Mohammed Akbar Khan, a man who had no reason to like or trust MacNaghten because he was the son of Dost Mohammed, the ruler deposed by the British in favour of Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk. On the second day of talks MacNaghten was dragged away and killed by Akbar Khan and his men, but not before speaking his last words in Persian: “Az barae Khooda” (For God’s sake).11 His linguistic ability was to no effect: the next day, MacNaghten’s decapitated and dismembered body was found strung up in the Kabul bazaar, an act intended to humiliate and undermine British power. The British, soon after, took their leave for India and in the Bolan Pass the army and its hangers-on were overtaken and utterly destroyed. Of the 16,000 soldiers and camp followers who had left Kabul in December 1841, only one man - legend has it - reached India alive: the others were killed, captured or sold into slavery.12

Although an old school Company servant, MacNaghten was interested in conquest and the continued expansion of the empire on behalf of the Crown and so he was to a degree in tune with the reformers. The positions for and against reform were however rarely fixed or consistent with the immediate interests of the different protagonists, whether Company officials, Crown appointees, missionaries and churchmen, Indian landowners, non-official planters or interloping merchants and traders.

The Prinseps, for example, were a family of orientalists, Company men in the main, but also reformers in their own way. They had an important influence in Bengal between 1780 and 1843: seven brothers in India had attempted to build back elements of the Mughal infrastructure both agricultural and administrative, in pursuit of good government. This was a sovereign responsibility that the Company had sorely neglected since winning the Dewany (the right to tax) with its victory at Buxhar in 1765, its sole interest being the extraction of as much wealth as possible whatever the consequences; and the consequences were to be horrific, the cause of (or contribution to) a succession of famines in which tens of millions died. The Prinseps were more enlightened thinkers and they were makers too: they struck coinage and drained swamps; they built irrigation canals, saltworks and docks; analysed populations, financed capitalist enterprises and reformed land laws; they transcribed ancient South Indian scripts, painted watercolours and wrote novels and verse. Of course, whatever their virtues, the Prinseps promoted the policy of colonial expansion too, but they nonetheless despised the idealism and dry abstractions of utilitarianism as not fit for this or any other purpose. William Prinsep wrote in his memoir about a party attended by his brothers on January 1st 1838: “a large New Year’s family dinner party at Charles’ house the chief amusement of which being the fun that Thoby and others made of Macaulay’s new [penal] code, which had just been issued by the Commissioners, which was so truly Benthamite and ingenious in its illustrations that is was called the Comical Code.”13

Macaulay had his own insults, describing his colleagues’ wives as ‘disagreeable’. One of these wives, Maria Millett, was an enthusiastic participant in William Prinsep’s amateur dramatical productions, as was her brother Edmund. One side mixed with the other. They were of course also William’s relatives, this being how Calcutta worked, and in this case through William’s wife, Mary Campbell. Mary was Elizabeth Hunter’s niece and the daughter of her sister Margaret, two of of the four remarkable daughters of Ross Jennings, the indigo planter, the other two being Eliza’s grandmother, Sarah Wintle, ‘The Great Grandmother’ of her poem, and Lucy Ruspini, who had married the eldest son of the world’s first celebrity dentist, the larger-than-life Bartholemew Ruspini, surgeon dentist to George IV, philanthropist on the square and provider of tooth powder and mouthwash to London’s poor. The Hunters and Ruspinis were both connected by marriage to the powerful Ord family of Northumberland, and so it went in the intricate web of East India Company families.

Like the Jennings sisters, William Prinsep was a child of indigo. His father, John, had made his fortune establishing the indigo trade in India. Ross Jennings (who, if he ever made a fortune, lost it) claimed to have owned the first indigo factory in Bengal and James Hunter’s father, Robert, may also have been in business with Prinsep and Jennings during his time as a merchant in Calcutta; their sons, William Prinsep and James Hunter, were co-executors of Ross Jennings’ eccentric will which bequeathed little money but had many codicils for the distribution of worthless possessions to his different offspring.

According to a Prinsep family history, Ross Jennings had notable but illegitimate ancestry that could be traced back to the first Duchess of Marlborough, Sarah Jenyns, and her sister Frances: both had positions in the restoration court of James II.14 Frances, known as La Belle Jennings, was a famous beauty; Macaulay in his History of England describes her as “beautiful Fanny Jennings, the loveliest coquette in the brilliant Whitehall of the Restoration” (he was surely unaware that Maria Millet was her relation).15 16 Sarah was Maid of Honour to James’ daughter Anne, and when Anne gained the throne Sarah was made Mistress of the Robes, Groom of the Stool, and Keeper of the Privy Purse and so she became the power behind, before and either side of the throne. Sarah and her husband, John Churchill, were made first Duke and Duchess of Marlborough by Queen Anne, who they had supported in the teeth of opposition from William and Mary. The Jenyns sisters’ aunt, Mary (Dolly) Jenyns, also moved in high circles, having had an affair with the Duke of Monmouth, the eldest of 14 illegitimate sons of Charles II. The union — a short one — resulted in the illegitimate birth of Thomas Jennings, the great grandfather of Ross the indigo planter; and so it goes that it was the aunt of the first Duchess of Marlborough, not the sister, who established this particular branch of the Jennings dynasty - a bastard line descending from the Stuart royal house.

The Jennings men were often less successful than the Jennings women. The Duke of Monmouth’s protestant rebellion against his uncle, James II, was crushed by Sarah Jenyn’s husband, John Churchill, proving that restoration family life was complex. The Jenyns/Jennings women were remarkable for their intelligence, their beauty and their ambition, which was still evident in Eliza’s time and after: in the beauty of Eliza’s mother and sister, in the intelligence of Eliza, and in their ambitious habit of marrying eminent Victorians. No less than three Jennings offspring married Prinseps (William’s younger brother Thomas married Mary’s sister Lucy, and his son Edward married Elizabeth Hunter’s daughter Margaretta); Ivy Dundas, a great granddaughter of Sarah Wintle, married the radical turned arch-imperialist Joseph Chamberlain; another married the Scottish lawyer and antiquarian George Seton; and Florence Eliot Campbell, Eliza’s niece, married William Ewart Gladstone’s first cousin Cecil. William Gladstone was a politician who was always scrutinised closely by Eliza Ogilvy for any hint of hypocrisy, of which she detected many.

William Prinsep, after his return to England in 1842, would be an important figure in the wider network in which Eliza participated, joining her husband on the Board of the Great Western Railway as Company Secretary, where he put to work the knowledge of finance capital, infrastructure and company management that he had gained in India as a partner in Carr Tagore & Company. William was principally a merchant, business manager and banker, but like his brothers Charles, George, Thoby, James, Thomas and Augustus, he was a polymath and a committed amateur in a breathtaking range of artistic and scientific pursuits. Outside business, William Prinsep is best known as a water colourist and lithographer, tutored by that incorrigible bankrupt, the artist George Chinnery; he was also a producer of musical and theatrical entertainments in which his friends and relations, including Maria Millet and Edmund Wintle, were enthusiastic participants (See Chapter 5, Dancing and death).

William Prinsep’s talents as a designer and engineer are less well known but by no means less exceptional. As a keen yachtsman on the Hooghly river he designed ‘a safe life boat, by adding an air pipe of tin’ around the gunwhale of his skiff: ‘a precaution I strongly recommend to all who indulge in boating for even if she fills with water, she cannot upset unless the air pipe be imperfect’; and so he invented the self-righting lifeboat. William also re-engineered the grand piano: I ‘had at this time just received from Stodart the new grand piano constructed on my hint with counteracting metal tube bars to prevent the block which bears the 3 ton of strain by the strings from twisting and flying out of the square. It arrived perfectly and was afterwards adopted by the whole trade’; and he experimented with early cast iron structures, having purloined ‘a shipload of cast iron girders, 24 feet long, and a model for that application in the construction of flat roofs, particularly wanted for India where the great heavy wooden beams were always giving way, either by rot or by white ants. It was a simple method of adapting flat arches of the thin brick of India to tea [T] girders.’ The military board, by rejecting Prinsep’s plan for constructing barracks with cast iron as ‘too heavy’, spurred him on to show the government officers ‘how completely they were in the wrong’. William built a range of silk store rooms and offices: ‘with the assistance of Native artists … I erected a complete range of warehouses at the back of our offices. The first floor being of these girders on arches, the second floor being covered only with a lighter roof as a protection against rain, using of course the cement in the arches and when well settled and dried, I found that it bought [bore] any weight without a single crack or settlement anywhere. All the world came to look and examine and the military boards so entirely approved of them’.17

True to the spirit of the Victorian age, Prinsep was remarkable for his ingenuity and self-confidence. He recognised few boundaries to ideas or ambitions and was able to utilise his talents in engineering, the arts and business. Inspired by everyday observations and acting with pragmatism and genius, he combined both old and new means — whether technical, human or financial — to give his ideas material form.

Early in his career, in the 1820s, William’s business acumen and eye for value became evident as a young merchant buying silk ‘under the noses’ of Company factors who in those days still dominated the trade. He became adept at understanding quality and pricing, trading with Indian and Parsee silk merchants whom he came to like and trust.18 He was taken into Bengal’s largest agency house, Palmer & Co., and made a partner. The agency defaulted in 1830, the first in a cascade of failures with a two-fold cause, according to William: a protracted recession caused by the 1813 Company Charter Act, which ended the EIC’s monopolies without stimulating a compensating increase in free trade; and a huge increase in the cost of debt resulting from the Company borrowing to fund its war against Burma at rates no one else could afford to pay — and so swallowing up the available capital in Bengal. William was bankrupted, but when he was discharged in 1836 he walked straight into a partner’s seat reserved for him at Carr, Tagore & Co. by his friend William Carr, also lately of Palmer & Co., and his father’s former business partner, Dwarkanath Tagore, a leading Bengali landowner and industrialist.19 Tagore had both the imagination to identify new business opportunities, and the charm and powers of persuasion necessary to attract the finance and government support they needed to succeed.20 It was Tagore who introduced an integrated industrial infrastructure to Bengal and with his partner Ram Mohun Roy promoted an enlightened and indigenous approach to education and religion. It was Tagore who brought the machine into the garden: iron, coal, steam railways and shipping. For the next decade he dominated commerce in Bengal, and played an influential role in politics, sometimes in uneasy alliance with ‘non-official’ Europeans against both the East India Company and its monopolistic tendencies, and also those who would reform it on behalf of Crown and free trade (ie. British) interests, such as Thomas Babington Macaulay and his Black Act. One consequence of these alliances was an unlikely public row between Tagore and Eliza’s father, Abercromby Dick, that played out in the pages of Calcutta newspapers during 1838, three months after Eliza’s arrival in Calcutta.

Eugenia W. Herbert: Flora's Empire: British Gardens in India. Edward Clive was the son of his more famous father, Robert, victor at Plassey.

Bence-Jones, Mark: Palaces of the Raj, Routledge 1973

Sriram Venkatakrishnan, Madras Heritage, on the Government House demolition, 2008 to make way for the Tamil Nadu Government Hospital. https://sriramv.com/2008/05/17/government-house-demolition/

Bence-Jones.

Maitland, Julia: Letters from Madras, during the years 1836-1839, London 1846

Robert Dick to William Fleming Dick 15th March 1839; MacNabb archive BL

Examples from both services can be found in the ceramics collection on the sixth floor of the V&A in South Kensington, about 50 yards apart

1834, Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay, Volume I By Sir George Otto Trevelyan

William Dick, unpublished letter to James MacNabb 12 July 1820, MacNabb Archive, BL

Perry, James: Arrogant Armies, CastleBooks, 2005 p. 121

Dalrymple, William: Return of a King, Bloomsbury 2013

This was Dr William Brydon, and East India Army doctor, the sole survivor of 16,000 who entered the northern end of the Khyber Pass, who arrived alone at a British sentry post in Jalabad on 13 January 1842. See https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/butler-the-remnants-of-an-army-n01553

Prinsep, William: Memoirs Vol 3, BL. Charles and Henry Thoby Prinsep, two elder brothers, were senior Company servants

De Principe July 1923 Family History James Prinsep, mss BL

Hamilton, Anthony (1713): Mémoires de la vie du comte de Grammont (in French). Cologne: Pierre Marteau. OCLC 1135254578. – Princeps (for "la belle Jennings")

Macaulay, Thomas Babington: (1855). The History of England from the Accession of James the Second. Vol. III. London: Longman Brown Greens & Longmans

Prinsep: Memoirs Vol 2 p18-19, 21

“most of my dealings were with native merchants in the (country) whom I never saw and to whom I sent advances (of money) freely without once meeting with dishonesty or failure in return. (This would not do today.) Civilisation, alias Europaration, has made too rapid strides”.

Tagore is an Anglicised corruption of the Bengali name, Thakur.

Kling, Blair B: Partner in Empire, Calcutta 1981, p162