8. The Bengal renaissance: great expectations, strangled at birth

The Bengal Renaissance of the 1830s and '40s was an alternative economic and cultural legacy that the British empire chose not to nurture, but to crush.

Dwarkanath Tagore was an immense character in all kinds of affairs in Bengal, not just as a businessman; he was a social reformer, philanthropist and clever political agitator and he emerged in the 1830s as a civic leader able to present a forward-looking agenda for Bengal. Tagore was possibly the first to do so since the shock of the defeat of the Mughal armies in 1757 and ’64. This narrative of a new Bengal was co-authored by his friend Ram Mohun Roy, the social, educational and religious reformer who had campaigned against the caste system, Sati and in favour of rationalist education in the English language; but Roy is best known for the Atmiya Sabha, an association promoting monotheist Hinduism which, like Unitarianism (not to be confused with Utilitarianism), had the goal of bringing religion into the modern age. Roy’s tomb, in Arnos Vale cemetery in Bristol, is within a mausoleum designed as a Chhatri by William Prinsep.1 A third member of the group was Tagore’s cousin, Prassana Kumar Tagore: he ran the press, legal and organisational side of Dwarkanath Tagore’s various undertakings which in their entirety were like a prototypical Kairetsu. These three formed the leadership of a movement that has come to be known as the Bengal Renaissance, a collective effort to modernise, industrialise and to an extent reclaim Bengal in the three decades leading up to 1846, the year of Tagore’s untimely death in England. Tagore’s principal ambition was to push India forward from the crude, mercantilist economy created by the East India Company, into an Anglo-Indian joint industrial enterprise with all of the necessary capital formation, infrastructure and institutions to sustain it. This was an alternative future for India as a creator of value rather than as a sink to be drained; it was a future that would not come to pass — and then in much reduced form — for 50 years and more after Tagore’s death, when it was centred on Bombay rather than Calcutta. The Bengal Renaissance was a possible legacy that the British empire chose not to nurture but to crush.

Tagore is, from a historical perspective, a complicated man: subtle, practical, adventurous, risk-taking in business (sometimes too much so, for William Prinsep, but Tagore could have said the same about him), careful in forging alliances to achieve his ends, by no means an idealist, a man who has prompted the question of his legacy: which side was he on? The answers include ‘his own’, ‘the British’, ‘the Indian nation’ (a concept that barely existed in his own lifetime), or something a little more precise: he was on the side of a positive and more enlightened future for the people of Bengal, in the context of the reality of the political, military and economic forces they were up against — or could exploit — as he saw it.

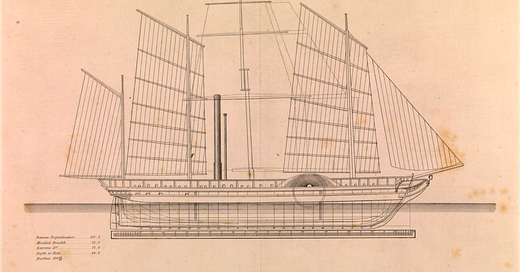

Steam power was such a force. The Ganga and Hooghly rivers were the highways of lower India but they flowed in only one direction - to the sea. In certain seasons it was impossible or highly dangerous to navigate upstream. Tagore organised the vertical and horizontal integration necessary to bring steam power to Bengal and Bihar and thereby two-way navigation and, in effect, to begin the industrialisation of North Eastern India. In 1836 he established a coal mine at Raniganj in Burdwan, North West of Calcutta, a region rich in both coal and iron ore, to supply his ships and Calcutta’s iron foundries. Subsequently Carr Tagore bought up other mines in the area to establish a virtual monopoly for its subsidiary, the Bengal Coal Company.

The General Steam Navigation Company, Steam Tug Association, Calcutta Docking Company and Bonded Warehouse Association completed the core transport infrastructure, controlled by Carr Tagore through majority holdings in multiple investments of different sizes and composition. The Company also invested in the commodities to be transported, processed, stored and traded to the world: sugar, salt, tea, indigo, cotton, opium. Tagore created the insurance companies and banks to finance his broad portfolio of independent businesses and protect against risk; and he also invested in forming opinion, buying up newspapers (and newspaper men) to promote his ideas, causes and alliances to the wider public in Kolkata, Patna, Dahka and of course at one remove in London too.

The management of such a diverse range of businesses was a challenge that was shared between a group of Indian and British managers, including William Carr and William Prinsep, both formerly of the great Agency House, Palmer & Co. Prinsep acted as entrepreneur and troubleshooter, taking a series of interim management roles to overcome specific problems in the docks in Calcutta, the coal mines of Burdwan and latterly the tea plantations in Assam. His talent was for administration, not so much technology, where he was a mere amateur and according to one chronicler of the Bengal Renaissance, Blair B. Kling, “Prinsep’s major shortcoming was his incompetent handling of technical problems. Again, his most valuable contribution was his liaison with government officials. Both in Calcutta and Assam he worked out complex details concerning legal position, production facilities and land tenure rights, and skillfully guided the new company through the sheafs of official red tape”.2 William Prinsep’s fate was described as being ‘a modern industrial manager born into a pre-industrial economy’; however, the man who made this assessment, A.C. Staples, knew nothing of Prinsep’s later career in which he brought back to England what he had learned in India.3 In Britain, a modern industrial economy was being created and sustained in a way that Bengal’s couldn’t. British industry had the protection of trade and access to capital (much of it derived from profits made in India) necessary to survive through the early years and thrive. What Britain lacked — because it wasn’t just an emerging industrial economy: it was the first industrial economy — was a management class with the kind of experience Prinsep had gained working at Carr Tagore & Co. within diverse connected industries. The beneficiary companies were the South Devon Railway and subsequently the Great Western Railway, where as the Company Secretary William organised its administration, policy and the immensely valuable business of distributing South Wales coal.4

The Anglo-Indian partnership that was created by Tagore lasted for nearly two decades, through the 1830s and ‘40s. During this time it dominated business in Bengal and as such it was unique in British India, in that this was a partnership based on equality and mutual respect. Shared political influence was exerted by Tagore and the Prinsep family on the East India Company; the economic control of the business was largely in the hands of Tagore, but with the advice of Carr and Prinsep. “Tagore’s congeniality, his intimacy with the British, and their high regard for him were of incalculable value to the firm. His personal qualities no less than his material assets help to account for the primacy of his house in the business world of Calcutta”.5

The result was that Carr, Tagore & Co transformed from a typical agency house into an entrepreneurial organisation of many facets, initially with the enthusiastic support of William Bentinck, the Governor General of India. The great strength of Carr, Tagore was its ability to innovate: to identify potentially profitable markets and conjure up ideas of how to serve them by combining capital with different technologies, processes, partners, managers and labour. This is never a simple equation, with many variables and unknown contingencies, often involving expensive experimentation through trial and error to get the answer to new questions right. How much power did a steam-powered tug need to take a barge upstream on the Hooghly river? The first mover may have to pay the price of getting the answer wrong. Because Carr Tagore had captured control of such a large share of industrial activities in Bengal, however, its managers obtained a uniquely detailed view of the entire universe of production and consumption and so could learn quickly. Those from England took that knowledge back home.

Ultimately the partnership was unable to capitalise on this potential. Carr Tagore was at times overstretched and suffered business failures, the most serious of which was that of the Union Bank. The risk of failure was all the greater in a region without the appropriate legal structure to protect investors: there was no legal concept of a limited liability company in Bengal at that time, one that had fostered the growth of British industry, as had trade protection, which in Bengal was restricted to the activities of the EIC. This became a double jeopardy for Carr Tagore, which had enjoyed a substantial but limited supply of local capital from Calcutta agencies and Bengali landowners, but was nonetheless reliant on finance from the EIC and English investors, and this was constrained by the fear of competition that existed in the minds of English and Scottish ‘free traders’ or competitors such as the Pacific & Orient shipping line, founded and led by Arthur Anderson — a later actor in this story — who took extreme pains to suppress Carr Tagore’s threat as a competitor in passenger and mail transportation across the Indian Ocean. In short, the great expectations of the Bengal industrial revolution were strangled soon after its birth by British capitalists and administrators with a determination to ensure that a crown colony should never be anything more than a marketplace for British manufactured goods and a source of only primary commodities: agricultural, mineral and human.

The charge that racism was a factor in this determination has substance.

What applied in law — before and after Macaulay’s Penal Code — later extended into the world of business: “No undertaking of magnitude in which other than local capital is invested should ever be embarked in, of which the sole and irresponsible control is placed under Calcutta management”.6 So wrote Rowland Stephenson in London in 1844 when promoting his Great Eastern Railway in Bengal, in opposition to bids by Carr Tagore for a Great Western Railway and another proposed railway in Bombay. Stephenson recommended that, to avoid business failure, ”the chief management of such important undertakings . . . be retained in England." The Court of Directors in London concurred, although opponents to Stephenson noted with sarcasm that he “recommends that all power should be lodged at home — where no companies were ever mismanaged and where bubbles are unknown”.

Over time, the racist stereotyping became ever more assertive and deluded: in 1851, the Reports by the Juries at the Great Exhibition complained that Indian prosperity was retarded by “the inert, careless, and indifferent habits of the natives confirmed and kept up by religious peculiarities and long-established prejudices”. Reporting on the Exhibition, ‘The Times asked why India’s mineral wealth was “not more efficiently explored and cultivated”, and concluded that “there is a field in India for profitable employ of Anglo-Saxon energy and skill combined with capital” … The Illustrated London News, likewise “dismissed the cotton mills and gins [in India] as primitive contrivances of the rudest class, to which . . . few or no additions or improvement have been made for centuries, showing how much remains to be done, when the light of civilisation shall have made its genial influence felt by our Oriental brethren”’.7 This was said of a country that had shown Britain the way in making fine muslins and chintz richly patterned in Asian motifs, all to be plundered by British manufacturers and renamed for cotton towns such as Paisley.

The effect on Indian business, especially after Tagore’s sudden and early death in 1846, was twofold: it strangled the supply of capital and it destroyed the multi-racial social and business networks that had been able to grow and prosper. Tagore’s son, Debendranath, had turned away from business and towards religtion; his son, in turn, was Rabindrath Tagore, the man who shaped Bengal’s cultural renaissance across the second half of the 19th Century and first half of the 20th. According to Kling, Tagore’s error was to misread the nature of British commitment to India … Dwarkanath established the house and invited Carr, Prinsep, and other impecunious British merchants to join him in the use of his capital. They had nothing to lose and everything to gain by accepting his offer, and they left for home as soon as possible. William Carr had departed for England in 1841.8 William Prinsep left India for good in 1842 having set up India’s first commercial tea venture as a joint Anglo-Indian enterprise, under the management of Maniram Barbhandar Barua: his experience is a measure of the decline. Maniram was the son of a high ranking minister of Upper Assam and had been Prime Minister to Purandar Singha, the titular ruler of Assam, from 1833-38, and subsequently Dewan (land agent) for the Assam Tea Company. Prinsep reported to the Company: ‘‘I find the Native Department of the office in the most beneficial state under the excellent direction of Muneeram, whose intelligence and activity is of the greatest value to our Establishment.”9 Under Maniram’s leadership local zamindars and peasants played the principle role in establishing the tea garden alongside British capital and science. However the alliance couldn’t outlast Prinsep’s return to England, suggesting that his preference for equal partnership was exceptional, not the rule. Locals reported that Maniram ‘retaliated with interest when a British employee slapped him’, and was dismissed. ‘Another tale has it that Maniram’s establishment of his own tea estates offended the Assam Company. Allegedly he was suspended on charges that he had purloined his employer’s seed and labour. Ironically, a number of new tea estates were established by the Assam Company’s British employees, who liberally pilfered its resources’.10 When in 1853 the Crown was forced into making one of its many enquiries into the iniquities of colonial rule (as a means of deflecting criticism) Maniram delivered ‘a stinging rebuke of colonial policies for bringing unprecedented suffering to Assam’. This did not go down well. In response Justice Mills branded Maniram as “clever but untrustworthy and intriguing,” and he was kept under surveillance’.11 Collaborative Anglo-Indian business relationships had seen their day. In 1858 during the First War of Independence Maniram was executed for inciting the young Raja, Ahom Saring Raja, to rebellion’.12

The destruction of the Bengal renaissance was much more than a business failure. Implicit in Tagore’s vision was a democratic ambition for national self-determination; it contained the idea that a post-mercantile India would be a nation with certain rights to determine how — alone or in partnership — it raised, applied and managed capital and also how it regulated its own markets (and its own education, civil law and religion). Such notions were put down with great determination by financiers in London, manufacturers in Britain and eventually English and Scottish traders in Kolkata too.

It might be interesting in the light of Eliza Ogilvy’s interests in the two countries to make a comparison with Italy, a new country previously divided into city states or provinces governed by imperial satraps (like India) but which until 1600 had been a central node in European and global manufacture and trade (like India), which in its northern half, after the Risorgimento, industrialised rapidly and especially in the period 1896-1913. In 1870 its GDP per capita was half that of Britain: in fifty years it made up the gap, albeit with one half of the country left behind at the periphery.

This was quite unlike India, which suffered the reverse fate, to be reduced and not to grow either its own industry or political independence for exactly 101 years. Instead, India would be a captive market for British goods, a garden to be harvested, a labour force to be super-exploited on plantations at home and abroad (in Mauritius, Ghana, Kenya, Trinidad, Guiana…) and any pretensions to establish an industrial base were suppressed.

Next chapter: William Prinsep in Canton, caught with his hand in the tea bucket

9. William Prinsep in Canton, caught with his hand in the tea bucket

On one of many hot nights in July 1838, William Prinsep stood on the ghat looking out at the Hooghly River; it was 4am and he had a splitting headache. This was two weeks before Eliza Dick and her sister Charlotte would arrive in Calcutta on the Lord Hungerford,

Subscribed.

An open, elevated, domed pavillion

Kling, B.: Partner in Empire, Firma, Calcutta 1981

Staples, A.C.: Memoirs of William Prinsep, Calcutta years 1817-1842, The Indian History and Social Review, 26/1 1989

When William Prinsep joined the GWR in 1848, his former partner William Carr took over his position as Secretary of the South Devon Railway.

Kling

Kling

Swift, A.: 'The Arms of England that Grasp the World':Empire at the Great Exhibition’ ex.PLUS.ultra Vol 3, April 2012

Kling p78

Guha, A.: Colonisation of Assam: Second Phase 1840-1859 Gokhale Inst. of Politics and Economics, Puna 1967

Sharma, J: Empire’s Garden, Assam and the Making of India, Duke University, Durham 2011

Sharma, J

Dutta, Dr. Anima: Maniram Dewan and the revolt of 1857 in Assam, MNC Balika Mahavidyalya