Research update: How much money did Scotland squander on the Darien scheme in 1698?

Historians using RPI are getting the answer to this question wildly wrong. The cost of a basket of goods adjusted for inflation veers increasingly from the truth the further back in time you go.

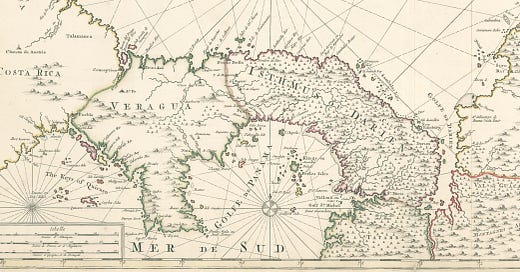

The Empire podcast with William Dalrymple always inspires a thought. The lightbulb fired by last week’s episode on the Darien scheme was that surely £400,000 invested in 1698 was nothing like the equivalent of £66 million today, as was suggested in this and almost every other account of how Scotland’s colonial fiasco forced an unwanted Union with England.

Today, would the loss of £66 million coerce a nation of 1 million people into relinquishing their sovereignty to an aggressive and untrustworthy neighbour? That’s just £66 per person — less than a tankful of petrol. Today, £66m wouldn’t buy a single street — if the street was Moray Place in Edinburgh — but £400,000 might buy an entire City in 1698. Even the 1400 Darien investors, who stood to gain from England’s repayment of the Scottish national debt, having collectively lost some £233,000 in the misadventure, would have received on a per capita basis only £60,000 in the modern RPI equivalent. Something’s wrong with the comparison, and it’s an error derived from the inappropriate use of the retail price index as a comparator. RPI is a basket of goods the cost and value of which can be compared over time using an inflation calculator; the value ascribed to such goods has however been so transformed by the multiple technological, economic and social revolutions experienced in the last 300 years (agricultural, colonial, steam power, factory systems, electricity, semiconductors … ) that the comparison has lost all useful meaning. Poor old RPI can’t keep up.

The reason why is that while the basket remains consistent, and thereby comparable, the things people use their money for are very different: there is no consistent equivalent to a mobile phone, a fork lift truck or a ticket to the Costa Brava. There are other measures, and measuringworth.com is a good place to start. I’ve always felt slightly uncomfortable with the alternative comparators at measuringworth because they multiply RPI outcomes by factors of 10 or 100 and more, depending on how far back you go, which seems outrageous and daring and not at all conservative and normative in the way that RPI is, and this is possibly why historians feel comfortable with sticking with it. But The Darien scheme episode and the thoughts it inspired gave me confidence that the further we go back in time (through all of those revolutions) the more important it is to ask questions about relative positions in society or the nature of transactions. ‘There is no single "correct" measure, and economic historians use one or more different indices depending on the context of the question’, says measuringworth, which makes different comparisons on the basis of the kind of expenditure being made and the value received or expended based on the cost of labour, the proportion of wealth or the economic cost of a project. The best description of how to apply the different measures is here. RPI may be a reasonable basis for a shopping trip for food or household goods, but not for the price of a car, for example, not least because it is a conveyance that didn’t exist in 1698 or in the 200 years afterwards. The nearest equivalent might be a carriage and two- or four-in-hand, for which conveniently I have the price of £150 (in 1800) for the carriage and an annual running cost of around £50 for the horses, feed, stabling, grooms and drivers. For that £200 in 1800, measuringworth.com gives a ‘real price’ of £20,400 (that’s a bundle of goods a typical household might buy, using RPI); it gives a labour value of £291,100 (the wage a worker would need to buy the commodity or service); a relative income value of £268,300 (an amount of income relative to per capita GDP, so someone earning £200 in 1800 would be in the layer earning £270k per annum today); and a project value of £1.5m, being the share of GDP represented by that amount of money.1 The income or wage value is probably the most relevant comparison in this case because because a coach was accessible to only 0.1% of the population in 1700, so like a lamborghini, not a Kia. However the project value is probably the most relevant to the Darien Scheme, and on this basis the cost to Scotland was not £66m; it’s impact on the Scottish economy would have been, as far as it is possible to make such comparisons, in the region of £12bn.

Darien was not a £66m shopping trip, but a fabulously large capital investment in creating a new colony and the exploitation of trade (and plunder) that might arise from it. The comparable size of that investment today — that kind of project — could be considered as the amount necessary to transport and provision 3000 settlers in three flotillas - or waves of emigration - and the equipment and materials to build and sustain a colony and the arms to defend it against competitors or indigenous people displaced. The opportunities for such an enterprise are infinitely more limited in a much smaller world today but if the target was Darien itself (where there are still no roads and few people) say as a land-bridge alternative to the drying-up Panama Canal, or the Arctic, or deep under the sea - still a relatively unexploited place - it would indeed be at least the £12 billion measuringworth.com suggests as an equivalent share of GDP, and probably considerably more. Darien was not unambitious.

Another way of looking at this problem is to consider what Scotland or the individual investors might have done instead with the £233,000 they spent and lost (out of the £400,000 raised) and what this amount represented in terms of national wealth. A number of accounts describe the Darien investment as equivalent to 15-40% of Scotland’s ‘capital’ or one quarter of its ‘liquid assets’. Much of this money had been squirrelled away for a rainy day and was doing very little for the economy, until the fever unleashed by the Darien prospectus persuaded 1400 Scots to empty their strongboxes and chests. In the previous 14 years from 1681-1695 the entire amount the Scots had invested in manufacturing had been just £17,000. In 1698 Scotland was recovering from years of famine and was desperately poor, relying for trade on its partners in Sweden, the Netherlands and France and shut out of the lucrative East and West India trades by England (mostly things I would not know today without the wonderful Empire podcast). A loss of, let’s say, the consensus of 25% of surplus capital would have been a sore blow in terms of opportunity cost: fishing fleets unbuilt, wharves unmade, houses and factories not constructed, land undrained. To lose one quarter of Scottish savings today would cost £33.5 billion (500 x our RPI equivalent of £66 million).2 In 1698, for the individual investors to lose £166 (the average share of £230,000, the opportunity cost of economic output would be equivalent to £8.85 million each, in 2023 terms.

England was relatively much wealthier than Scotland, after 40 years of rapid and continuous growth in GDP. England was investing large sums in colonial enterprises and reaping rewards, so that by 1700 the English sugar trade — a single commodity — was equal to two thirds of the ‘equivalent’ of £398,000 that England used to pay off Scotland’s debts as part of the agreement on Union. By 1700 incomes in England earned from the Caribbean and American trades were equal to 3% of GDP, so around £2m: this is more than five times the price paid for Union, seven years later.

We can imagine that a majority of that 3% of GDP would have contributed to savings and thereby surplus capital, readily available to invest in Government bonds and pay for the Union. In Scotland, £400,000 felt like ‘nearly everything’. In England it was a fraction of the free cash arising from colonial enterprises.

What makes it really hard for comparisons to work across centuries is the huge change that has taken place in the distribution of wealth and the cost of things previously entirely unavailable to the vast majority of the population: health, sanitation, manufactured goods, leisure travel, applied arts, exotic foodstuffs, books and newspapers, etc. etc. These were available only to a tiny minority - the minority investing in projects like the Darien Scheme.

To understand the relative impact of income or expenditure, we have to ask the right questions about who was involved and what were their intentions. We need to explore not necessarily the comparative cost of a basket of modern goods at Sainsbury or Walmart (can this become a last resort?) but in the Darien case the cost of a comparable project, not necessarily an investment in colonial expansion but one with equivalent cost, reward and risk. Likewise, we might ask what that investment meant in terms of income relative to GDP, or the proportion of surplus capital available that had been foregone to take this opportunity.

A final question: Why do so many historians use RPI calculators exclusively. This might be because they appear conservative; also they are used consistently by peers so form a constant measure (albeit a misleading one) using a consistent long term series of prices measured in GBP. But above all I suspect it’s because you don’t have to provide an explanation each time you use it; hat gets in the way of a good story, but not in the way of genuine understanding.

In 1800 a person stepping out of a coach to enter a shop would be a member of ‘the coach trade’, ie. those people so rich they didn’t even have to ask the price of a commodity, because they could buy whatever they wanted. This would have been the top 0.1% of earners. There are aspects of running a coach that speak ‘commodity’: hay. Others that speak to wages: the groom. But there’s an argument that because a coach requires its own infrastructure of manufacturer and repair shop, servants, power and housing (for coach, horses and staff), and is within the reach of only the highest earners in a society, it is more comparable with a helicopter than a mid-priced Kia or, if we stick to 4 wheels, a Lamborghini. In terms of the proportion of the population who could afford to buy and operate the coach, the £1.5m comparison seems to be more relevant than the paltry £20k in terms of the relative cost of the conveyance (and convenience) and the proportion of the population to which it is available.

This number is based on current UK savings of £720bn, of which Scotland’s portion would be roughly £134bn, of which £33.5bn is a quarter.