The remarkable Captain sisters, organising women's resistance to British rule in India

Dadabhai Naoroji paid for his granddaughters to have the very best education at Oxford & the Sorbonne; they used it wisely, to lead the women's Satyagraha movement and the boycott campaign in Bombay.

This unlikely story is of four women — one Anglo-Scottish, three Parsi-Indian — leading parallel lives with very different outcomes. The story emerged after an enquiry made at the Bodleian Library into the provenance of a photographic print of a portrait of Eliza Ogilvy. I mentioned that Eliza’s granddaughter, Ella Ogilvy Bell, had been a librarian at the Bodleian in 1910 after graduating at St Hilda’s College, and I was sent a spreadsheet with the names of all of the women studying at the University of Oxford between 1879 and 1920: Ella’s name was there, recorded as matriculating at St Hilda’s in 1906. But there was another name next to hers that grabbed my attention, whereupon a deep and many-chambered rabbit hole opened up.1

Ella Ogilvy Bell was keeper of her grandmother’s manuscripts, letters and her commonplace books. She was one of an early cohort of women to study at Oxford University and, of the five women who entered at St Hilda’s in 1906, two were born in India: Ella was one — like Eliza she was born in Muzzafarpur, in Bihar, where her father worked as a railway engineer — and the other was Nurgis Naoroji, born in Kutch, Gujarat, the granddaughter of Dadabhai Nairoji, the MP for Finsbury Central who served as the President of the Indian National Congress three times and will forever be remembered as ‘The Grand Old Man of India’. He was a Parsi from southern Gujarat and an early proponent of the theory of a ‘wealth-drain’ from India to Britain, an idea that had a profound impact on Congress and the struggle for independence.

The primary mechanism for the drain of wealth from India to Britain between 1765 and 1938 was the use of Indian tax revenues to pay Indian producers for their goods for export to Britain and then often re-export to Europe, Africa and the Americas, thus recording a surplus for Britain but not India. These goods were sold in London (or their final destination) in return for rupee denominated bills of exchange against deposits of gold, sterling or the payee’s own currency held in London. In this way the value of virtually India’s entire trade surplus was captured in Britain, so that India — a net exporter — recorded a trade deficit, while the bulk of Indian taxes were used to pay for British government expenditure, not Indian. This was a kind of double larceny (by a thief in a clever disguise) that involved paying people for goods with their own money and pocketing all of the surplus wealth generated. The total wealth transfer from 1765 to 1938 has been calculated by the political economist Utsa Patnaik as having a present value of £9.2 trillion, a figure she considers to be ‘highly underestimated’, because it uses lower-than-market interest rates and excludes the enormous debts that Britain imposed on India after 1858, during the Raj. For Congress and the independence movement this description of the mechanism by which wealth was transferred from India to Britain was a galvanising discovery. The great significance of this wealth transfer was not that it created stupendously rich British nabobs, but that it generated sufficient surplus capital to invest in labour saving machinery and thus stimulate the industrial revolution. Nick Robins writes: “Drawing on recent analysis carried out by Utsa Patnaik, the Asian drain grew as a proportion of Britain’s gross domestic product from 1.7 per cent in 1770 to 3.5 per cent in 1800. Crucially, from 1800 onwards the Asian drain began to match the enormous extraction of wealth that Britain had historically achieved from the slave-based sugar plantations of the West Indies. Together, the combined surplus in 1801 was equivalent to over 86 per cent of Britain’s entire capital formation from domestic savings.”2 This is the capital that powered the second phase of Britain’s industrial revolution, providing much of the £3 billion spent on building the railways from 1845 to 1900; it became apparent that Empire and the industrial revolution were intrinsically linked together; and we are quite reasonably able to say that India built Britain’s railways, not the other way around.

Oxford University was founded in 1249 and its introduction to women as students not servants was 630 years later. In 1879 two Oxford colleges, Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall, started accepting women undergraduates — 21 in total. St Hilda’s did not admit women until 1893, at most half a dozen a year, and as two of just five women who matriculated at the college in 1906, Nurgis Naoroji and Ella Ogilvy Bell must have known each other well. Both were born in India, but the common ground they shared may not have extended far beyond the sub-continent of their birth and the rare conjunction of their presence at St Hilda’s College: two young women could hardly have experienced a more profoundly different life experience or way of seeing the world.

Nurgis Naoroji was the third of five sisters, the daughters of Dr Ardeshir Naoroji, all remarkable and highly educated at the expense of their grandfather, Dadabhai Nairoji, who was indeed “that man [among but not of the Hindoos] who would have the courage to bring forward his wives and daughters to be instructed upon European principles of education” .3 He funded the education of the girls and their two brothers. In Parsee society women share a status equal with men in family, education and social life. Meher, the eldest of the siblings, studied at Edinburgh University and had the distinction of being its first Indian woman to graduate in medicine; Goshi, the second, studied English at Kings, London, then at St Anne’s, Oxford, from 1908; Nurgis, as we have heard, studied at Oxford, but only for one year and for most of that time under the watchful eye of the Special Branch; Perin, the fourth daughter, was a student at the Sorbonne in Paris where she focused her energies on revolutionary activities; and Kurshed, the fifth, trained in Paris as a classical soprano with a promising career which she abandoned in the 1920s to work with Mohandas Gandhi.45

Goshi said, in an interview recorded in 1970, when she was 86 years old: “In 1899 my grandfather wanted to give us the highest type of education and so he sent for my eldest sister, myself and my brother to be educated in England. I joined a private school, called Tudor Hall, near the Crystal Palace, with my older sister … I went from the school to Cheltenham”. At Oxford, “I took my degree in English Language and Literature and came [back] to India in 1911”. On her return from Europe with Perin the sisters rendezvoused in Bombay with Nurgis , who had travelled up from Ceylon, and a period of intense struggle against the British Raj began, quite literally within minutes of their arrival.6

Goshi was the organiser; Perin the firebrand, principle agitator (Gandhi called her ‘peppery sister’); Nurgis was involved in the independence movement throughout the 1910s, ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s but ill health prevented her from taking part in activities that risked jail where - said Goshi - she would have certainly died; instead, she became the secretary, messenger and letter writer, communicating between the sisters and Gandhi and Perin whenever they were imprisoned, which during the boycotts of the 1930s was often.7 Collectively, these three became famed as the Captain Sisters having married three brothers in Bombay — all lawyers — with the surname Captain.

There is a photograph taken at the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly Circus, apparently on 14th September 1906, of the Shahenshai Navroze banquet of the Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe, with at least two of ‘the Captain sisters’ attending8. Their grandfather, Dadabhai Naoroji, is the guest of honour, standing at the centre of the top table, Seated next to him, on the right from our viewpoint, is the Parsi revolutionary, Madame Bhikaiji Cama; Goshi is the woman on the left of the top table, Perin on the far right9. The woman to the left of Dadabhai Naoroji may be Nurgis. On the extreme left of the picture is a man with a very strong resemblance to Mohandas Gandhi, dapper in a black tuxedo sitting next to a woman who looks very like his wife, Kasturba. This dinner would have been shortly before commencing Michaelmas term at Oxford University if the dates on the caption are correct. Goshi was at Kings’ College at the time, Perin visiting from Paris, Nurgis would be just about to take her place at St Hilda’s. Gandhi, however, was in the Cape, and didn’t travel to London until some months later: if the date in the caption is correct, it isn’t him.

After a preceding ZTFE event, in March 1906, Perin had been denounced to the police by an informer. “In a private letter from a person who was present at the Jamshedji Navroj (31st March) I hear that Miss Perin A. D. Navroji [sic] grand daughter of Dadabhai Navroji did not stand up when the King’s toast was drunk and her conduct caused much criticism. This young lady … has been known to freely express anti-English sentiments, and even threats in private company”. Such is the pettiness of the secret policeman, writing from the Criminal Intelligence Department in Bombay to the Foreign Department in Simla on his typewriter with a distinctive broken ‘x’ key, a feature of many of the reports on Perin, Goshi, Nurgis and Madame Cama.10

Much worse (from a police point of view) Perin was accused of violent sedition. “Information received shows that Perin Naoroji and one or two others are being instructed in the manufacture of bombs by a Polish engineer named Broniesky… I hope you will have Perin watched on her arrival in India most discretely and carefully. She will be writing letters to Madame Cama but these will be addressed to Madame Cadeau; please do not interfere with their transit as I hope eventually to get them”.

In 1907 Perin lived with Madame Cama at 144 Boulevard Montparnasse. Cama was a member of the French section of the Workers’ International, associate of the Indian revolutionary Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who was extradited to London by the French. ‘She had extensive connections with Irish, Egyptian, Polish, and Russian exiled revolutionaries in the French capital, travelled among French socialists Jean Jaurès and Jean Longuet and joined the Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière. Cama also espoused the struggle for Indian independence among international feminists and suffragettes, combining anticolonialism, socialism, and feminism into a unique articulation in Bande Mataram, a new periodical she had founded with Har Dayal in September 1909’.11 In 1910 Perin crossed over the Channel from France with Mrs Cama and Savarkar and was seen with him by police at Victoria Station. Goshi complained later: ‘In fact that put us in the bad books of the British’ and it caused problems later. Perin and Goshi were identified in a police report: ‘She hailed Savarknr with greetings of “Bande Mataran”, and other revolutionary epithets … Her Sister Gasasp [sic] is a student at Oxford and was only staying in London for a short time during the Easter vacation.’12 Goshi recalled: ‘After we returned to India, they wouldn’t let us remain in any post for long, because their collectors or their political agents thought that we were ladies with “very advanced views” and we should be got rid of’.13

In 1910, on their way back to India, Perin and Goshi accompanied Mrs Cama to Brussels to attend a national congress of Egyptian nationalists as the only female delegates. The event had international significance, with attendance from some 150 Egyptian anti-imperialists including Mansour Rifat, and prominent European socialists and Irish revolutionaries, with the Naoroji sisters representing India and Perin singing the event out from the stage. From the conference they travelled onwards to Ceylon, where they met Nurgis, in January 1911, then travelled north to Bombay by boat and train.

Later in the same journey, the three sisters together in India, Goshi recalls: ‘There was only one compartment to hold seven ladies. There were four English women and they stood at the door — it was very hot at 11 o’clock in the morning, and they said, “you can’t come in here.” … and I said “But why not? Three seats are vacant.” “Oh for the simple reason that you are black and I am white”. So that put my temper up and I said “I prefer to have my colour and my manners.” So the good lady thought that she had caught a Tartar, so she disappeared.’

‘Then as we went to the door, some girl not dressed at about 10 in the morning said, “please don’t come in we are so uncomfortable”. I said “I cannot help it and the way that lady spoke to me I mean to get in”…….She cried “Call the station master, I hope he is a white man”. And the station master was as black as my boot and standing behind me. He came forward, clutched at the door and said “Madam, these ladies must get in”.

‘One good lady had an open revolver in front of her, because I was very upset and I said, “to be treated like that by a foreigner in our own country is disgusting!’. So the woman said, “Did you hear that? Foreigner! That is sedition! Pure sedition!”. That was our first experience of racial arrogance, because in England we were treated with deep affection’.14

After their return to India Mohandas Gandhi became an increasingly important figure in both the independence movement and the sisters’ lives. Goshi first met Gandhi in 1906 at a party on a boat on the Thames. ‘Gandhi-ji was dressed in very smart European clothes with a diamond tie pin….He wanted me to go to Africa and go to Jail. I being young and very frisky said I didn’t believe in going to jail in foreign countries. We would free our country first”. In 1915, when Gandhi returned to India from South Africa for good and visited Dadabdai Naoroji at his house in Bombay, he met Perin whom he described to Goshi as ‘a golden person’. From 1920 Perin took to wearing khadi and began working for the nationalist cause in earnest, breaking with Savarkar’s revolutionary violence. All three Captain sisters transferred their allegiance to Satyagraha and khada; their lives came to be dominated by opposition to the violent police repression that accompanied the Rowlatt Act in 1919, the shock of the massacre at Jalianwala Bagh and the civil disobedience movement that erupted in the 1930s.

The sisters threw themselves into Congress work. In 1921 Perin and Goshi were founder members of the Rashtriya Stree Sabha, the women’s branch of the independence movement; Perin was General Secretary, Goshi a Vice President and Nurgis joint Secretary responsible for correspondence with foreign organisations. Theirs was an education well used.15 Through the political volunteer wing of RSS, the Desh Sevika Sangh, they led the boycott of British goods in Bombay in 1930.

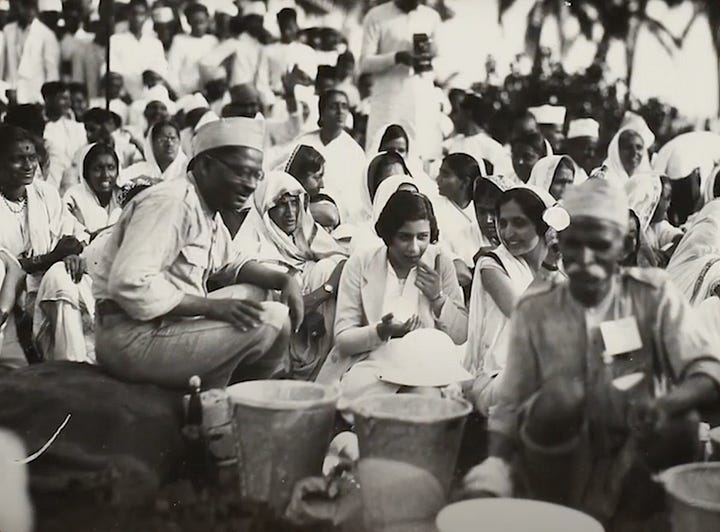

The sevikas dressed in saffron saris, sometimes hemmed with the colours of the national flag. They picketed cloth markets and alcohol stores and they manufactured and auctioned salt. Initially more than 800 women from all sections of society were actively marching and picketing, subject to attack by lathi-wielding British and Indian police and facing constant arrest and in some cases imprisonment. Their strength in the face of such repression eventually shamed the traders of the Mulji Jetha - the largest market for foreign cloth in the East - to seal up their stocks or send them out of India. This was a huge victory, albeit temporary. The Bombay textile and liquor boycotts had operated as a pincer movement with Gandhi’s salt march to Dandi, with one attacking British trade, the other its tax collections, and both had providing a vivid illustration of the methods by which the British oppressed India and drained its resources. Repression increased, and in May 1932 an outbreak of sectarian Hindu-Muslim rioting struck a blow to Congress’ prestige and certain merchants resumed trading British cloth. The Sevikas took to the markets again and by August most trading ceased.

Gohsi was jailed at least three times under the emergency powers act and on another occasion while travelling as a representative to Congress in Calcutta. Perin was jailed five times, once for seven months.16 Her first arrest came at a significant moment in the civil disobedience movement, on 3rd July 1930 on the fourth day of Boycott Week in Bombay. The Municipal Corporation of Bombay passed a motion of protest against her arrest by the British regime: ‘When Perin and other women activists were released from prison, a mile long chain of about 5,000 women led by Sevikas welcomed them back. There were crowds of women reportedly 10,000 strong at both ends of the parade. Such active participation of women in the freedom struggle was in part possible because of the example and the leadership of Perin and her compatriots’.17

By December 1931 both the RSS and DSS had been banned, proscribed as illegal organisations. This was matter of pride to the leadership of the women’s movement, as a measure of the effectiveness of their work, and a political achievement made entirely independently by women in every aspect of the struggle. A leaflet distributed on Independence Day 1934 by the Ghandi Seva Sena - the successor organisation to the Desh Sevika Sangh, concluded:

“Freedom can only mean freedom for the masses. It can only mean the well-being and happiness of the masses. Never before in living memory was the condition of the people as miserable as it is to-day - and this is particularly so in the case of our agriculturists, who are living in a state of chronic semi-starvation and inconceivable poverty.

“We feel that if we stand united and follow the path chalked out by our great leader MAHATMA GANDHI, we must succeed. There is no room even for the thought of failure. We are certain that our cause will soon triumph.

Bande Mataram

Parinben Captain

Jamnabe Purshotam

The two authors were arrested for their defiance18.

Back in Europe, on the other side of the world, Ella Ogilvy Bell struggled too, towards different ends but also — as she saw it — in the cause of justice. She was a forceful and independent woman and after 1915 she was seeking out the truth of her husband’s death. Ella left Oxford in 1910 with a third class degree in Classics and in 1914 she married Geoffrey Tomes, a Lieutenant in the 53rd Sikh Regiment, soon to be despatched to fight Pathan tribesmen on the North West Frontier.19 Together they had embarked for Bombay in 1914, but stayed only one year, called back by the First World War. Tomes’ regiment was one of many destined for Gallipoli where his death was caused — twice over, in a sense — by Winston Churchill. Geoffrey Tomes died on 10 August 1915 on the heights of the Chanak Bair ridge in Gallipoli, fighting with the 1/5th and 1/6th Gurkha Rifles against the Turkish Army. Why Churchill? Not only was the disaster at Gallipoli — like Narvik, in the Second World War — one of Churchill’s ‘bold strokes’ incompetently executed, but also the First Lord of the Admiralty had used his position to arrange for his brother, Major Jack Churchill, to be appointed to General Staff HQ in Tomes’ place, forcing him back to the trenches. Tomes’ war diary recalled: “I am going to the 5th Gurkhas to-morrow as one Churchill is coming to take on this job. I am not sorry as it is much more fun I think with a Regiment instead of under the nose of a General all the time.”20 Two weeks later he was dead.

Ella Ogilvy Tomes also used her education to effect, to discover what really happened on the Chanak Bair ridge and why. She wrote to all of the officers involved in that two-week period, receiving detailed statements which she compiled into an 18 page typed report that reads like a court of enquiry.21 Using her husband’s own diary and the testimony of Lieutenants Erskin, Cumins, Knowles and Cosby, Captains Phipson and Milward, Major Tillard and the commanding officers of the two Gurkha regiments, Colonels Firth and Allanson, Ella painstakingly recorded the planning and progress of the assault on the 3000ft precipitous mountain ridge rising up from the sea. The battle took place over five hot August days, fought against a regrouped force of the 19th division of the Turkish army commanded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the future founder and first President of the secular Turkish Republic; and so with Atatürk, in front of him and Churchill to the rear, Tomes’ fate was sealed.

Ella’s enquiries deconstructed the steps towards disaster: they revealed that the general staff had resisted but failed to prevent the replacement of Staff Captain Tomes — who excelled at his job — by Staff Major Churchill, who was an unknown quantity with a powerful patron; they revealed that intelligence had underestimated Turkish strength - “they are in a bad way … the next fortnight will perhaps finish the Turks all together”; that Tomes participated in a night attack on the 6th, troops had lost touch with each other in the gullies and maquis, the Turks had commanded the heights with machine guns throughout. After reaching the lower summits they came under heavy Turkish fire and spent a day pinned down in a ditch under a low wall in the hot sun, before escaping down the ridge in the dark. This was with the 1/5th Gurkhas. The 1st Battalion 6th gurkhas had taken the highest point on the ridge, furthest forward and isolated, under constant attack and all of their officers killed or wounded. On the 9th Tomes received orders to take command of the Battalion. Within 10 minutes of arriving he was killed. He was buried in a shallow grave with his kit but not his letters, which were retrieved, and there he lies still. That was the limit of the gains by the Indian Brigade. Attaturk’s Division strengthened the ridge and made it impregnable, and it wasn’t until 1918, with the complete surrender of the Turkish army, that the site once again became accessible to the British.

Ella was in Rouen in French Normandy in 1915, working as a nurse in a Voluntary Aid Detachment in the railway marshalling yards. This was the main British supply depot to the Western Front; she was serving coffee to British and Indian soldiers and taking their statements about the terrible battle at Neuve Chapelle, which she recorded carefully in a notebook which can still be read today in the archive of the National Army Museum.22 Later she moved to Wrest Park Hospital in the New Forest, a country house converted to treat badly wounded soldiers. In the Second World War she returned to New Bodleian Library as Head of Registry in the Prisoner of War Department. Nurgis, at the same time, was with Gandhi at the Panchgani hill station, South East of Bombay.23 For both of these two women, it was a long way from St Hilda’s in 1906, rowing on the Isis, and dining at the Criterium Restaurant.24

To read the prequel of this story, go to On the education of young women

If you’re new to Eliza Ogilvy’s Commonplace Book, the Prologue is a good place to start

© William Owen 2024 - All rights reserved

With thanks to Judith Siefring at the Bodleian Library.

Nick Robins, The Corporation that Changed the World, 2012, London p206

This is a quotation from an unnamed individual in the Bengal Herkaru, 8 June 1850. ‘The day is far distant for this happiness to be conferred on my countrywomen. I would give something to see that man, among the Hindoos, who will have the courage to bring forward his wives and daughters to be instructed upon European principles of education.’ Bengal Hurkaru 8 June 1850.

A history of the family’s education is given in a Criminal Investigation department police report of 8 December 1910: “Mr. Dadabhai Nowroji had a son named Dr Ardeshir who died some years ago, leaving four daughters named Miss Meherbai, Miss Perin, Miss Nargez, Miss Goshi, and one son named Jal [there were five daughters, three sons,]. All these children received a very good education in England under Mr. Dadabhai. Miss Merherbai arrived in Bombay with Mr. Dadabhai in 1907 and Mis Nargez followed some months after them. Mis Parin remained in Paris to study French and Music and Miss Goshi in London to study higher English. From confidential enquireis [sic] made it has been learnt that both Miss Parin and Miss Goshi are coming to Bombay with their brother Jan in the beginning of this month but they have not yet arrived here”]

Kurshed worked in the North West Frontier provinces promoting non-violence, hindu-muslim unity and political consciousness amongst Pashtun tribes involved in banditry and kidnapping, often in grave danger of her life. A Naoroji family tree can be found at https://dinyarpatel.com/naoroji/family/

Interview with Goshi Captain, 16 July 1970, CSAS: “Mrs. Goshiben Captain … tells Uma Shanker of her activities in the Freedom Movement, Desh Sevika Sangh (the women’s wing of the satyagrahis) in the Civil Disobedience Movement, the Bombay Pradesh Congress Committee, the All-India Village Industries and the Hindustani Prachar Sabha” https://www.s-asian.cam.ac.uk/archive/audio/collection/g-captain/

Letter form Gandhi to Goshibehn Captain, Sevagram, August 5 1945

Brochure, gala ball London 2011, on the 150th Anniversary of the Zoaroastrian Trust Funds of Europe. The Persian New Year is celebrated at the end of March, but in India in March and and also late August or early September.

Information kindly provided by Dr Nawaz Mody of K R Cama Oriental Institute, Mumbai, and Malcolm Deboo, President ZTFE

Foreign Department, Bombay Police, Notes in the Criminal Intelligence Office, December 1910-June 1811, National Archives of India. Copies kindly provided by Dr Dinyar Patel.

Ole Birk Laursen ‘Anarchy Or Chaos: MPT Acharya and the Indian Struggle for Freedom’. Hurst, London, 2023; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virendranath_Chattopadhyaya

Bombay Police 12 May 1911

Goshi Captain interview, CSAS

Goshi Captain interview, CSAS

Miss Naju Dastur, Draft Report on Desh Sevika Sangh 1930-31 BL, IOR:MSS EUR F341/167

Dastur, Appendix 1, BL

The Bombay Chronicle, 4 July 1930, https://savitanarayan.blogspot.com/2021/01/perin-naoroji-captain.html

A copy of the leaflet is included in the All India Congress Committee files and reports on Desh Sevika Sangh and Gandhi Seva Sena 1931-34 IOR:MSS EUR F341/167

Not until 1920 did Oxford award full degrees or University membership to women. The exam conditions and questions were the same as for men, but the degree mark had no official status.

Geoffrey Tomes’ unpublished war diary, National Army Museum. 1966 - 02 - 22 - 4&4

Ella Ogilvy Tomes, notes and transcribed letters on the death of Geoffrey Tomes, NAM 1966 - 02 - 22 - 3&4

Ella Ogilvy Tomes, personal notebook Feb 1915, NAM

Gandhi: The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Letter June 3 1945. Gandhi writes: ‘Kurshed [Nargis’ sister] is here. She is with Nargis. She will migrate to ‘Dilkhusha’ as soon as N. is gone.’ Dilkusha was the name of Gandhi’s house (is a Persian word, commonly translated as blissful, pleasing, delightful, etc.). In August 1945 Gandhi wrote to Goshiben: ‘Are you well? Peppery sister came, saw, conquered and went. I have discussed your scheme with Shyamlal. But you must do your part. Dordi never leaves its rigid shape, even when it is burnt.[‘

Anyone young and in the art world in the mid-1980s would have spent many nights under the newly rediscovered gold mosaic ceiling of the bar at the Criterium Brasserie in Piccadilly. For a brief period this was London’s most fashionable meeting place.