Introducing Eliza Ogilvy (the long edition)

A literary life; a network of artists, writers and scientists; a microhistory of the East India Company and its influence on British culture in the 19th Century.

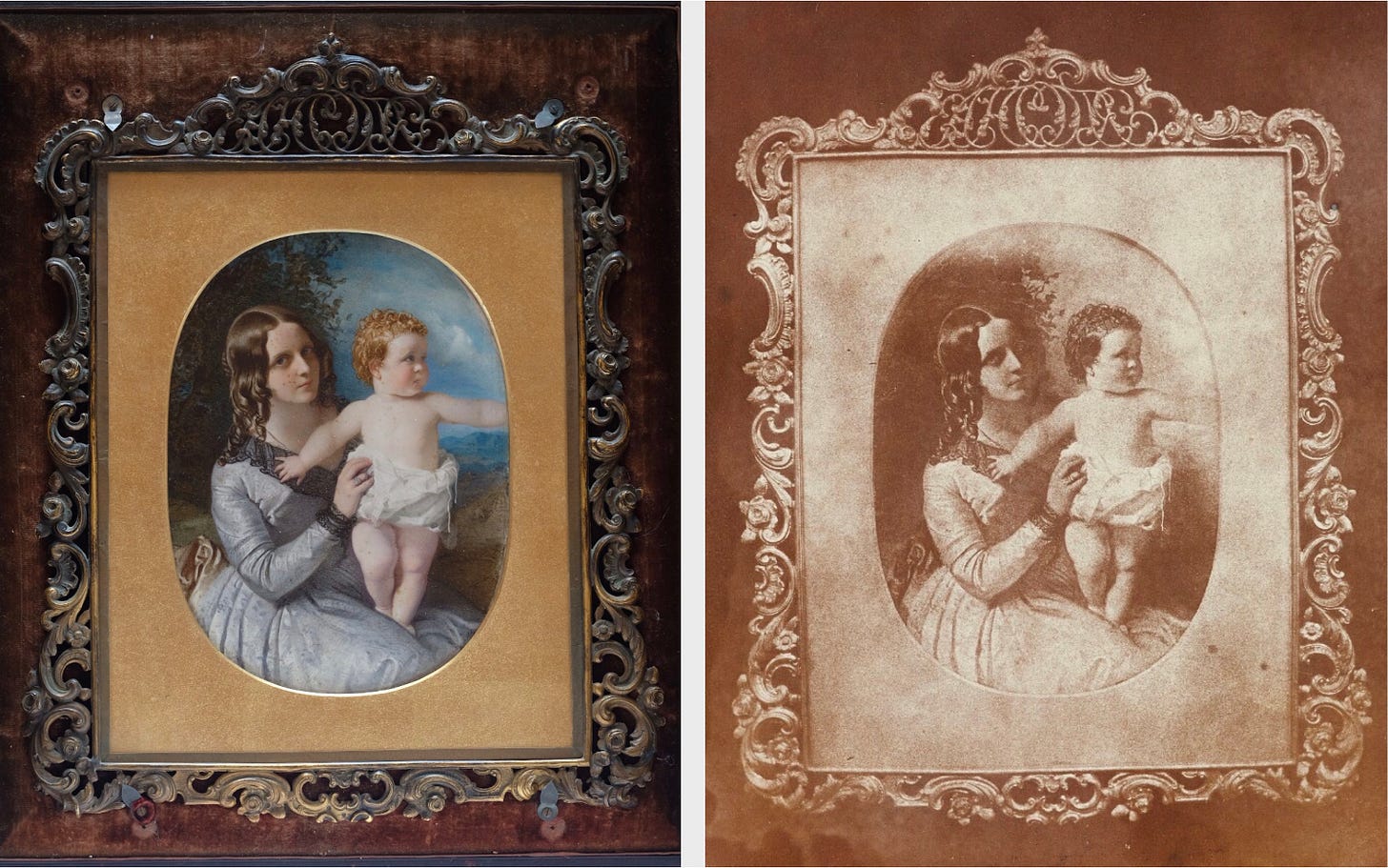

In 1845, the miniaturist Robert Thorburn — a great favourite of Queen Victoria — painted a portrait of Eliza Ann Harris Ogilvy and her first child, Rose. Eliza is depicted in half mourning, wearing a grey dress with black lace cuffs and collar, for Rose was painted posthumously. The painting is set within a cast bronze gilt frame, custom made, surmounted by a cartouche with the initials E.A.H.O. & R; a fashionable design that revives 16th Century Italian typographic ornament. The frame fits precisely into the purple velvet lining of a leather carrying case. This is an oversize miniature, but still portable. Miniatures were a way of connecting East India Company families through lengthy separations; copies would be made by engraving, printing and distributing to family members.

In 2017 the Bodleian Library launched the first digital catalogue raisonné of the works of William Henry Fox Talbot, and this included a photograph of the painting, credited to Fox Talbot’s assistant, Nicolaas Henneman, and dated 1847; it’s shown above on the right, next to the original. The discovery provoked two questions: what was the connection between Eliza — or Thorburn — and Fox Talbot? And how had the painting come to be photographed at such an early date in the history of photography? The Talbot family of Lacock was connected with Eliza’s via the Shakespears - ropemakers of Wapping who had become administrators in Western Bengal - but this was just the first of many red herrings. Then, in 2021, a New York dealer in 19th Century photographs informed the Bodleian of the purchase of a salt paper print of the same photograph, found pasted into the frontispiece of Eliza’s first published volume of poetry, A Book of Highland Minstrelsy, and this was added to the catalogue. The book was a presentation copy, given by Eliza to her friend, the antiquarian and art historian William Sterling of Keir; it has the following inscription: “The portrait of the Authoress, facing the Title Page, was Talbotyped by Mr N. Henneman from a miniature by R. Thorburn. W.S. London - Aug. 10. 1847”.1

And so it transpired that the Thorburn portrait of Eliza had been included by Stirling within a batch of copies and originals of 60 masterpieces by Spanish artists — Velaquez, Murillo, El Greco and others — to be photographed by Henneman for Stirling’s forthcoming book, ‘Annals of the Artists of Spain’. Not only was this the first comprehensive history of Spanish art in the English language, it was also the first history of art ever, anywhere, to be illustrated by photography rather than engravings, and so the photograph of Eliza’s portrait was created at the very moment in history when fine art entered the age of photographic reproduction. The incident is typical of Eliza. She was the sort of person that interesting things happened to, because she tended to be in the right place at the right time: in Calcutta in 1838, when her father became embroiled in the storm of protest against Macaulay’s ‘Black Act’; at Dunkeld in 1842, for the huge festival of tartan-clad chiefs and clansmen celebrating Queen Victoria’s first visit to the Highlands — to seal the knot with England; in Rome for carnival in the Spring of 1848, when the spark of revolution overtook the city; at the Great Exhibition in 1850, accompanying Elizabeth Barrett Browning, for whom it was all too much; and at the Crystal Palace in 1864 with Garibaldi addressing a crowd of 25,000 Londoners, her youngest daughter bouncing on his knee.

The life and times of Eliza Ogilvy and the extraordinary network of people she knew — writers, artists, antiquarians, engineers, scientists — is the common thread of this cultural history, also in part a family and literary history too, although perhaps not a conventional one. The thread crosses disciplines and points of view, and ranges over geographies from India to Scotland, south to Italy in the Risorgimento, then back again to Britain and the imperial culture factory that was the Crystal Palace at Sydenham.

Like a number of those involved in the Crystal Palace, Eliza had old Indian connections, as she called them — her family was active in India over 150 years and across six generations. A central theme of this collection of essays and observations is the East India Company’s rarely acknowledged influence on the massive generational shift that took place in Britain between 1780 and 1920, a period in which Georgians became Victorians then Edwardians, Scots became British, precarious gentry emerged as the well-to-do middle classes, and industry and colonial extraction replaced domestic agriculture as the major sources of wealth. These were the earliest days of consumerism, mass communication and travel, and of a new individualism driven by fashion and of course good taste: the latter being a guide to living in a world that had dispensed with time-honoured practice and tradition, and was an antidote to alienation. The people - and the objects and images they lived with, as well as the way they saw the world - could be described as modern, in every sense of the word.

Eliza Ogilvy was an accomplished poet and critic. She published five volumes of poetry and wrote essays and fiction for literary magazines, becoming known for her innovative outlook and for subject matter that broke the accepted boundaries of women’s writing; and yet perhaps her greater contribution was the ability to bring together interesting and talented individuals. What makes Eliza’s character exceptional is the breadth of her engagement with people actively involved with the great themes of 19th Century history, themes that are often treated erroneously as separate and distinct: the expansion of empire; the encouragement of new technologies of manufacture and mass communication; political struggle for democracy and national self-determination; and the emerging cultural dominance in Britain of a new middle class. This is not the traditional story of elitist reaction to machine manufacture, manifested in the embrace of medievalism and craft, but instead a technophile, scientific, orientalist and avowedly capitalist enthusiasm for new ideas in a world of vastly increased scope and scale — more steam punk than arts and crafts — a tendency rather than a self-conscious movement, one with its own set of impulses and contradictions.

In her teens, Eliza’s education in Edinburgh brought her into contact with the Scottish literary scene of the 1830s and ‘40s, “a flourishing and democratic counter-culture intent on re-establishing popular national traditions”2. On her return from a visit to India in 1838-41 and after her marriage in 1843, she mixed with physicists and antiquarians interested in optics and the arts who gathered together in the Edinburgh Calotype Club and the Athenaeum in Pall Mall. She was a vocal member of the group of expatriate English, Scottish and American poets — mainly women — in Florence during the Risorgimento, when Eliza and her husband David Ogilvy lived in Palazzo Casa Guidi in the apartment above their friends, Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: this is the role for which she is best known, but one that exposes the stark yet unspoken contradiction between her support for Italian self-determination and acceptance of her family’s role in the subjugation of India. Then, for two decades beginning in 1854, the Ogilvys were active participants in the Sydenham Set, a diverse collection of individuals who, as owners or employees, directed the design and programming of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham. There is a Zelig or Lanny Budd quality to Eliza Ogilvy’s life; it gives us a fresh and sometimes surprising view of the people and events that contributed to the making of British culture in the 19th Century, and in particular the strange and enduring influence of the East India Company not only in India, but on the making of the British middle class and its peculiar tastes and ways of seeing the world.

Eliza’s own part in the story is as a poet, critic and attractor of intelligent enthusiasts and leading lights. She was well known as “a writer of clever stories and able criticisms, as well as of spirited poems”3; but nonetheless, had it not been for the discovery of Elizabeth Barrett-Browning’s 37 letters ‘to Mrs David Ogilvy’, purchased by the Browning Institute in 1971, Eliza might have been lost to us, a forgotten figure of Victorian literature. This isn’t to say that Eliza’s literary flair was absent, just that — in the way of Sir Walter Scott’s or for that matter Elizabeth Barrett’s — her work was of a kind and of an age that we here and now have preferred to forget. A critic in the Spectator magazine, in a generally favourable review, could nonetheless write: ‘As a poet, Mrs. Ogilvy is not of the highest order … “thoughts that breathe and words that burn” will not be found in this volume … But Mrs. Ogilvy has one of the first qualifications for poetry or any other kind of writing: she has a knowledge of her subject, with the skill to select from it what is appropriate to the purpose’.4

This knowledge was kept and sorted in Eliza’s commonplace books, which held important clues to her own life, her friends and connections. Commonplace in this context doesn’t mean quotidian. The practice of common placing is described by Katherine Rundell in her biography of John Donne as: “a way of seeking out and storing knowledge, so that you have multiple voices on a topic under a single heading … one thought reaches out to another, across the barriers of tradition, and ends up somewhere fresh and strange … For Donne, apparently unrelated scraps from the world were always forming new wholes. Commonplacing was a way to assess material for those new connections: bricks made ready for the unruly palaces he would build.”5

John Donne was a common placer, Eliza Ogilvy too. She kept a succession of foolscap ruled notebooks containing her poetry, reminiscences of her family and a collection of scraps and memoirs of the extraordinary Victorians she knew. In the Armstrong Browning Library database, which catalogues all known publications relating to Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, the last of her commonplace books is a cypher, listed as item number L0220 but with a blank entry for the holding institution6. The commonplace books are indeed missing (bar one, rediscovered in March 2024) however the last was part-recorded, and a wealth of material remains about Eliza’s life and that of her connections, with a little searching. Eliza is not always the primary subject in this story but instead the common factor — the common placer — in a work that traces the networks of the people she knew, the events that engulfed them and the ideas they held onto. So, not a literary Life or conventional biography; instead, stories that surround Eliza, not just stories about Eliza; more a scrapbook that follows the example of her missing commonplace books, as a collection of in the main first-hand stories and micro histories drawn carefully together, with the purpose of ending up with a familiar but also different impression of the cultural impact of empire and industry through the long 19th Century.

Using Eliza and her network as the common factor connecting everything together is a helpful way of finding how one thing leads to another: imperial careers and family networks as a force for social mobility and the creation of a ‘British’ middle class; the manifest connections between capital, industry and empire that become strikingly apparent in the careers of Wellington’s colonels after 1815; how the death on the banks of the river Sutlej of Eliza’s uncle, Sir Robert Dick, was used to water the first ugly shoots of Christian militarism in British society; contrasting coalitions of opposition in Britain — emancipationists, nationalists, chartists and dissenters; Scottish outsider poetry, and it’s role in developing a democratic counter culture that included women as authors and contributors to social debate; the evolution of portraiture under the pressure of family separation, social mobility and technical innovation; the Bengal renaissance as an alternative future for India (and legacy for empire) snuffed out by racism, utilitarianism and protectionist ‘free traders’; a voyage to Canton and Macau with William Prinsep (the merchant trader), his meetings with William Jardine (the smuggler) George Chinnery (the artist) and swapping insider information on silk, opium and tea; a porcelain dinner service at Government House, Madras that defines a point on the path to the First War of Independence; with the Brownings in Florence, Bagni di Lucca and Venice, exchanging contrasting views on poetry and Louis Napoleon; critical writings on architecture and the arts as a guide to popular taste in The Ladies Home Companion; recreating the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, a strange amalgam of artists, engineers, orientalists and East India money.

Eliza’s final commonplace book was read and part recorded in 1973 by Peter Heydon, the co-editor of Eliza’s correspondence with Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Heydon photocopied six out of 104 pages: he says, “From various entry titles in Mrs. Ogilvy’s commonplace book we know she had become friends with a number of people associated with the community surrounding the Crystal Palace at Sydenham: Sir David Brewster, Henry Chorley, Anna and Susan Cushman, Helen Faucit, the actress, and Sir Arthur Sullivan, the composer of operettas”. They were part of the group of artists, writers, musicians, scientists, engineers and railway magnates who collectively governed the programme of concerts and events, the design of the great courts, the acquisition of objects, the making of the educational institutions at the Palace; these provided the populace with an immense and enduring novelty: not just a pleasure dome, the Palace was also a museum and university and a concert hall; it propagated entertainment, art, design and industry at a mass scale and to the people of Britain and the world with discrimination, panache and — some critics have said — with an occasional tendency to vulgarity.

At its peak in the late 1850s and 1860s the Sydenham set included Charles Manners Lushington, Arthur Anderson, and Eliza’s husband David Ogilvy: all three were directors of the Crystal Palace Company and they shared in common their powerful East India connections and ownership of significant holdings in railways and shipping. The Palace was situated firmly at the intersection of interests in mass travel, art, industry and India. Samuel Beale and Joseph Paxton were both on the board of the Midland Railway and of course Paxton was the architect of the Crystal Palace; there were George Grove, Henry Chorley and Henry Bicknell (musicial impresario, critic, curator); John Scott Russell, the organiser of the Great Exhibition and —with Brunel — the constructor of the steam liner the Great Eastern; Russell’s two daughters — both had affairs with Sir Arthur Sullivan; David Roberts R.A., the orientalist painter; and Owen Jones and Matthew Digby Wyatt, designers of the Great Exhibition and the courts of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham.

This convergence is now a largely forgotten moment in history when an interdisciplinary movement in British art and design emerged and achieved total immersion into popular culture, with an aesthetic that became so pervasive it is now all but invisible — unless, one day in Paddington Station you choose to look up and around and recognise the perfect synthesis of orientalism, lightness, repetition and machine power that it represents. The Sydenham Set enjoined artists and industrialists with a common interest in the transformative impact of new technologies of reproduction and transportation; this was a technophile and in certain respects progressive tendency, more interested in mass culture than elite production; its objectives included the education of popular taste in the manner approved by the guiding lights and trustees of the Crystal Palace — as representatives of the imperial establishment; its failure was to be characterised by contemporaries and later generations as populist and kitsch; and so to be eclipsed in design history by the Arts & Crafts movement, which represented an avowedly humanist but also elitist and retrograde tendency, spinning the myth that machine production is inevitably inferior to craft, and treading an alternative path — narrower, twisting, let’s call it the scenic route — towards the development of modernism in 20th Century Britain.

The other important survivors from Eliza’s last commonplace book are her memoirs of Marcelly Graham, her lifelong companion and mentor, and of her pivotal friendship with Elizabeth Barrett-Browning; these fill in the gaps of her early years and explain much about Eliza’s character and talent. Both manuscripts were transcribed in the 1970s by Eliza’s grand daughter, Ella Ogilvy Bell; each is a small masterpiece of the form; they are personal, insightful, critical, honest as to their subject’s character and circumstance, easily pursuing interesting tangents — but never too far — and every paragraph full of promise and peril. They are also as revealing about Eliza as they are about her subjects. According to A.A. Markley:

“Of particular interest … are Ogilvy's reminiscences of discussions between her husband and herself and the Brownings on the topic of poetry …. she writes of a philosophical disagreement regarding the purpose and use of poetry in their times; Ogilvy felt that poetry should be written for and aimed at the masses, while the Brownings argued that it should be intended instead for those of the "Higher Intellect" or the "Lords of Mind," who were then to take the responsibility of interpreting it for the common people (EBB Letters, p. 28).”7

Mass culture and the democratic impulse are common themes in Eliza’s life. She valued plain speaking and popular wisdom, often embedded in folklore, a subject she knew well. About the Brownings, Eliza said: “Nothing could be less democratic than they both were in poetry” (a statement that might be contradicted by an enthusiast for Aurora Leigh, but perhaps Eliza influenced Elizabeth in ways she hadn’t anticipated). For Eliza, nonetheless, there was always a contradiction between the democratic impulse of a small nation Scot and the assumption of inherent authority in an imperial Briton. This choice was always present, but rarely voiced. The peculiar structure and lasting impact of Eliza’s early life was determined entirely by the needs of the East India Company and the people she called ‘old Indians’. She was born Eliza Ann Harris Dick in Muzzafarpur, an indigo growing district in Bihar, and lived there as an infant for just a year before being deposited by her parents along with her sisters and brother in her uncle’s house at Tullymet on the edge of the Highlands, in the lands of the Dukes of Atholl where the choice of Jacobite or loyalist, Catholic or Episcopalian, Tory or Whig, was likewise never clear-cut or easy. Eliza was educated in Edinburgh and there she fell under the influence of Jacobite friends but was in adulthood a resolute protestant who bit at the heels of hypocrites but always defended family first — and family was totally dependent on England’s lucrative imperial project. Eliza grappled with the contradictions of being at one return, Scottish, rebellious and the progeny of precarious gentry, and at the other British, well connected and independently wealthy; the wealth was acquired at the expense of Indian tenant farmers and their labour and then invested, usually, in Bengal bonds, town and country property and the stock of British and French railway companies. Inside this unruly colonial palace we can explore the impact on British life of the East India Company, which was, let’s be clear, perpetrator of one of the most prolonged and widespread acts of global robbery-with-violence in human history, resulting in a reversal of fortune of unprecedented scale and inserting racism as a lens through which the British came to misunderstand the world.

These aren’t the only contradictions in Eliza’s life. Cutting through the bigger picture that is gradually revealed are small but persistent tragedies and regrets in personal life. Eliza’s high regard for marriage and the love for her husband (which was noted by the editors of her correspondence with Elizabeth Barrett) is no more than an appearance, or one that had became false in middle age. She was frustrated, and held back by her husband. The whereabouts of Eliza’s commonplace book may be unknown, but much of her unpublished poetry survives and tells a different story. Eliza’s last published anthology, Poems of Ten Years, was dated 1856 when she was just 34 years of age; however she continued to write verse until at least 1890 when she was approaching 70 and her sight was beginning to fail; and some of these poems are amongst her best work, some very personal, others political. Three poems written over three years, from 1885 to 1887, each one pierced with regret, speak of a great love lost in her late teens and early twenties, not long before she married David Ogilvy in 1843 when she was 21.

The private poems reveal a hidden side to Eliza, in which she is punished, worn down but stalwart. There is one called Rest, on the subject of her lost lover, written on the anniversary of the subject’s birthday, some years after his death but still a decade before David Ogilvy died; and another, Mismated, in which Eliza dreads the thought of being buried in the same grave as her husband, when ‘Only Death loosens that bondage of Hell’. Something was not right, and indeed it is hard to find evidence of Eliza operating in the public sphere after the great Burns Centenary gala at the Crystal Palace in 1859, to which she entered her poem that was highly commended by the judges, but after which she seems to fade from public life. (The exception is the publication of Sunday Acrostics, in 1867).

The unpublished poems merit close reading; and there is much that can be inferred about Eliza’s life from Elizabeth Barrett Brownings letters to her. Also, in the absence of the commonplace book there are other sources. Ella Ogilvy Bell was the family historian and a librarian at the Bodleian. She possessed manuscripts, documents, notebooks, photographs and a bust of Eliza by the American sculptor William Wetmore Story — the bust is now in Casa Guidi, the Browning’s former apartment in Florence. The extant family archive has some rich material, including long, lively and highly descriptive letters from Eliza in Rome in the Spring of 1848 (a month or two before she met Elizabeth Barrett Browning) and in Naples in 1850. In addition there are 17 unpublished poems written between 1844 and 1886 — mainly satirical, some deeply personal — and various recollections, portrait miniatures and daguerreotypes. There are also mementos: David Ogilvy’s annual first class director’s pass to the entire Great Western Railway network, dated 1879, the year he died; a lock of Eliza’s hair taken on their wedding day in July 1843; the bible given to her by her father in 1825, when she was just 3 years old, as he was leaving Scotland for Calcutta; and the badly singed manuscript of an Italian operatic libretto salvaged from the fire that destroyed the North transept of the Crystal Palace in 1866.

These documents and manuscripts, combined with internet archives, library research and family letters in India Office archives at the British Library, National Library of Scotland and University of Cambridge, have filled in many of the gaps left by the absent commonplace book, but also give room for speculations about lost stories of a voyage to India and absent character sketches of extraordinary people such as Sir David Brewster - the inventor of effective 3D photography and the kaleidoscope - or Helen Faucit, Arthur Sullivan, David Roberts R.A., and ‘Mrs Izett and trip to India’; even the two tracts by Eliza’s father, Abercromby Dick, on Religion and Weather8. These and other vital clues demonstrate that Eliza did not spring unformed into the circle of expatriate female English, Scottish and American poets in Florence during the Risorgimento, but had already enjoyed a remarkable education in the classics, art and architecture and in Scottish folk myths and storytelling, one that jarred with her family’s deep involvement in the East India Company, but had matured into a democratic point of view on the purpose and politics of her work which embraced national rights, political satire, identity and tradition, family and death.

And so a story that begins in 1778 with a meeting in a Highland grove between Edmund Burke and a young farmer’s daughter, much to the advantage of the Dick family, follows an arc across the entirety of the long 19th Century, which for Eliza travels via Muzzafarpur, Atholl, Edinburgh, Calcutta, Fitzrovia, Florence, Sydenham and Bridge of Allan. For her family too, it includes participation in the invasions of Afghanistan in 1841, Punjab in 1846, China in 1860, Asante in 1873, the Cape in 1900, Tibet in 1904, Iraq in 1917, Waziristan in 1920 — and this notwithstanding her brothers’, cousins’ and uncles’ involvement in the first war of independence in 1857-59 and the white mutiny in Bihar in 1883, each of which intrudes on this tale.

The story ends with Eliza’s death in Ealing in January 1912 just three days before her 90th birthday. In the years in between, the world had changed out of all recognition — the entire world, not just Eliza’s part of it — and her personal experience of that change might provide a fresh and challenging viewpoint as to what happened to whom, and how, and why.

© William Owen 2024 - All rights reserved

Inscription kindly provided by Hans P. Kraus Fine Photographs, New York. The provenance of the photograph was confirmed by Hilary MacCartney, with a copy of the original invoice from Henneman to Stirling, showing the cost of the photograph of Eliza’s portrait to have been 3s/0d. See Hilary MacCartney and José Manuel Matilla, Copied by the Sun, Museo Nacional Del Prado, 2016.

Gillian Hughes, in James Hogg’s Literary Friendships with John Grieve and Eliza Izett, by Janette Currie

Camilla Crosland, Landmarks of a Literary Life, London 1893.

L0220 Ogilvy, Eliza Anne Harris. Commonplace book. § Containing her personal reminiscences of interesting people she had met during the 1850’s and 1860’s and manuscripts of her own poems written during the 1890’s. Includes her recollections of the Brownings. § Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Letters to Mrs. David Ogilvy, 1849–1861, ed. Peter N. Heydon and Philip Kelley (New York, 1973), pp. xxv–xxix from the manuscript then in the possession of Mrs. Ella Ogilvy Tomes.

Katherine Rundell, Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, Faber, London 2022

The Spectator 1 March 1851, Page 17

Markley, A. A. (2001) "Eliza Ogilvy, Highland Minstrelsy, and the Perils of Victorian Motherhood," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 32: No. 1

India Office Library at the British Library; Centre for South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge