A peek inside the telegraph room at Governor's House, Madras, in 1918

Two photographs taken by Herbert Collingridge, Military Secretary to the Governor of Madras, reveal the information technologies underpinning imperial rule as WW1 drew to a close.

This is the telegraph and post room at Governor’s House in Madras (Chennai) in 1918, towards the end of World War One: two photographs taken from opposing sides of a room that contains the accumulation of technologies that transported news and information around India and eastwards to Burma, Malaya and China; south east to Australia; west to Arabia and Egypt, then to London — the city from which an empire that had reached a permanent state of crisis was controlled.

There was crisis in Madras. The outbreak of WW1 in 1914 ‘‘encouraged the malcontents to make trouble in the Presidency’’.1 Nearly 1.4 million Indian troops had been sent to fight in French mud and Mesopotamian sand for the continued prosperity of the British empire. Major Collingridge, who took these photographs, had recently returned to his post in Madras from Baghdad, where British forces had ousted the Ottoman Turks. His beguiling images of Governor’s House and its lake and gardens, grazing Blackbuck, white-clad servants and a solitary sentry, belie the truth that Madras was in the grip of an influenza epidemic and famine. Food riots broke out in the city on 8th September 1918, not because of a lack of grain, but because speculators had bought up the rice surplus from farmers; they were betting on a second harvest but the monsoon failed. The railway system, a British innovation, was built to carry surplus grain rapidly in bulk to ports to be delivered to the rest of the world, not to bring relief in times of famine. And so prices had soared, unrestrained by the Government’s laissez faire policy on trade; grain had suddenly and inexplicably disappeared from the markets, and by September, rice riots and looting had spread from the mofussil to the markets of the City of Madras.

The Madras Mail of 9 September 1918, reported:

“a rumour, the origin of which no one knows, but which ... is accepted as true by uneducated Indians (and indeed by many who ought to know better) that Government, with a view to relieving the food situation, are prepared to close their eyes to, if not actually connive at, the taking of the law into the hands of the people”2

This was not the case: laissez faire applied to trade, not public protest or looting grain stores; still, the riots and the looting began. The bells on the telephones in the post and telegraph room at Governor’s House would have been ringing off their pedestals.

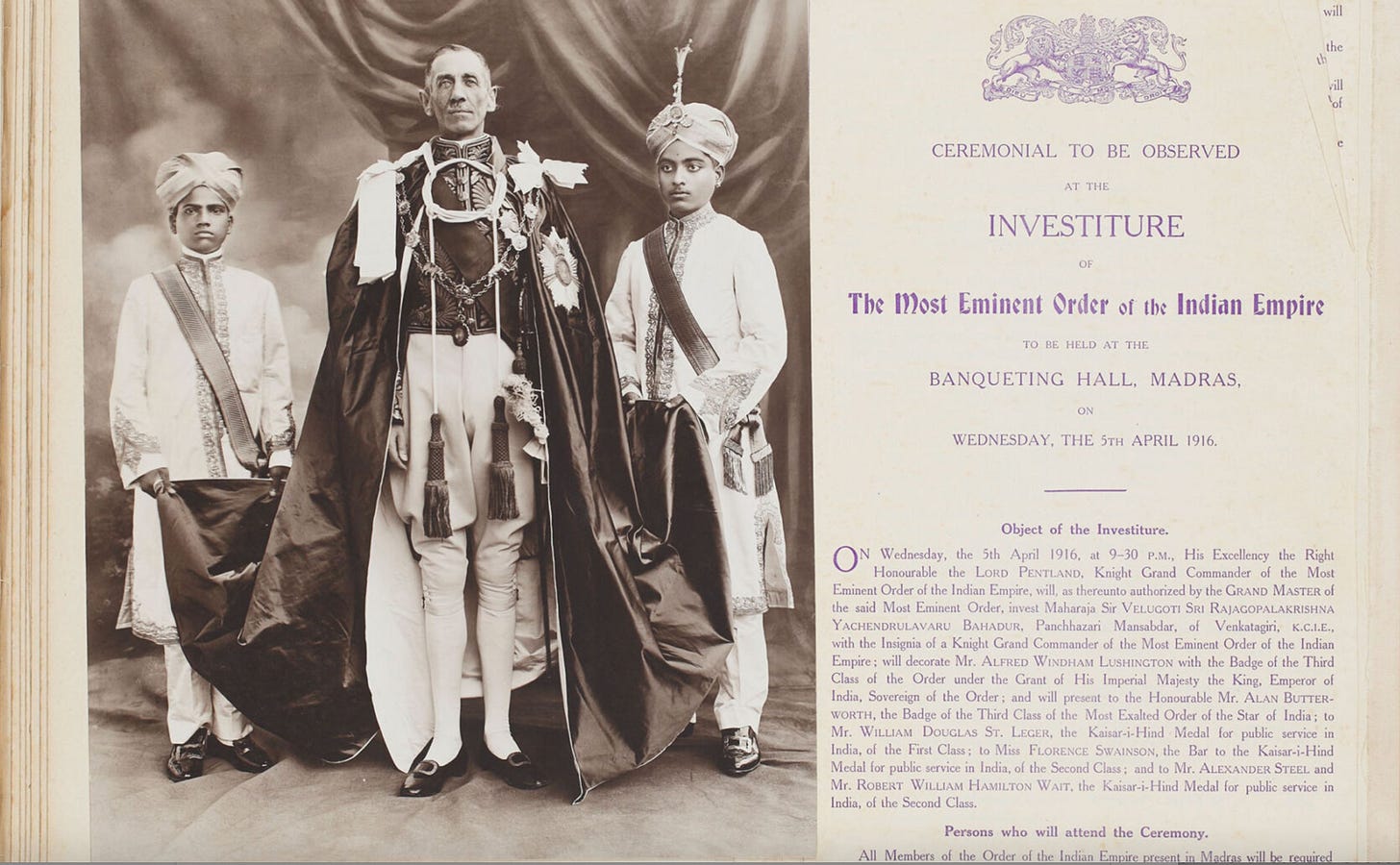

Look carefully to the left of the longcase clock, in the top photograph. There is a lectern beneath two electric sockets, each with voltmeters and probably installed within the previous decade; on it you will see copies of the Madras Mail and Madras Times — perhaps on that very day, the 9th September, and certainly close to it. Unfortunately neither their dates nor headlines are legible, but the sign below the longcase clock states clearly: “Madras War Fund, for sale, Rs250”.3 So the war carried on. In the second photograph, on its side in a bookshelf, we can see a fat Post Office London Directory 1918. We can date the photograph to no earlier than June 1918 (when Collingridge returned from Basra) and probably no later than November or December 1918, adjacent to the Armistice of 11th November 1918. The backstop is 31 March 1919, when the Military Secretary and his father (an indigo planter from Muzzafarpur) returned to London with the Governor of Madras, Lord Pentland, and his family in first class cabins aboard the SS Chindwara.

The Post Office Directory was a guide to the 7 million residents of London, containing private and business addresses and just 140,000 four-figure telephone numbers held by businesses and the few wealthy London residents who could afford a subscription to a phone line — just 2% of the population. In Madras it would have been mere hundreds. Not so long before this photograph was taken ink and paper were the primary means of communicating with the metropolis. The London Times would take four weeks to reach Madras. A reply to a letter required a three to six month turnaround — and that was in the days of steamships, never mind sail, which took a year. The advantage to Governors in India was to be granted huge if not absolute autonomy of action. The disadvantage in London was lack of control over any self-serving or incompetent impulses by a governing class on which Britain depended for the accumulation of immense quantities of free capital to fuel its unprecedented growth in trade and industrial production, and to pay for the Royal Navy.

Telegraphy and telephony transformed the levers of government. The two photographs taken by Major Collingridge illustrate a world in which that autonomy had evaporated and external grip was reasserted. The Governor of Madras no longer had the freedom to rule his Presidency without interference from Calcutta (Kolkata). This was a liberty removed in 1834, when Lord William Bentinck as Governor General of India was given authority over the three East India Company Presidencies; nor did he have freedom from interference from London, which had disappeared with the arrival in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1870 of the eastern end of a submarine telegraph cable that was wrapped around the world to link London with India, and so provide answers within the instant it took for questions to be discussed within the India Office, Cabinet Office or Parliament. Unlike his 18th and 19th Century predecessors, Lord Pentland could no longer rely on the three or six months of grace between making a decision in Madras and having it rescinded in London way too late in the day to make a difference.

The first of the two photographs is taken from the left of the longcase clock, the second from the right. The centrepiece of each is the desk on which sit four telephones. An easy (and not necessarily correct) assumption is that the three Magneto field telephones, each with a dynamo hand crank to provide power, are hotlines connected directly to the garrison at Fort St George, just across the Cooum River, and to identical rooms in Bombay and Calcutta. The bells can be seen to be powered by batteries on the floor; it’s all very Heath Robinson. The candlestick telephone without a dial (not yet invented!) would be connected to the Madras telephone exchange inaugurated in 1882 by the Oriental Telephone and Electricity Company, which opened at the same time as exchanges in Bombay and Calcutta.

India already had one of the most extensive telegraphy systems in the world in the late 19th Century, pioneered by the engineer S. P. Chakravarti. In 1850, an experimental electric telegraph line was trialled between Kolkata and Diamond Harbour as a means of getting the news first from ships entering the mouth of the Hooghly River, still a day’s steaming from Calcutta. Telephony grew more slowly, because the Government was reluctant to give up its monopoly on communications or to promote infrastructure manufacture within India. It was not that resources or expertise were absent locally; as always, in the unequal relationship between colony and metropolis, India would be the market for the essential equipment, Britain the source. The candlestick telephone on the desk in the post room appears to be a Table Telephone No. 2, manufactured between 1906 and 1959 by Ericsson at its factory in Beeston, Notts. It’s staggering, today, to conceive of an electrical device in production virtually unchanged (but for a dial) for 53 years.

But there is more to see and comprehend. The desk is accompanied by its essential partner, a leather upholstered upright lounge chair with armrests, a staple prop in the Victorian photographic portrait of eminent scientists and businessmen, of the kind taken by Maull and Polyblank in the second half of the 19th Century. The chair is a carrier for the status as well as the weight of its occupant — something of a throne.

Beside the chair is a raffia waste bin — or a snake charmer’s basket, if you prefer. There is an adjustable day calendar, regrettably hidden behind a telephone handset and so denying us a precise date. There are pigeonholes labelled ‘His Excellency’ and ‘Manager’, for distributing letters and documents; and behind the back of the chair two side tables, on one of which is a black steel box (top picture, far right) precisely identical to the strong-box in which Eliza Ogilvy’s manuscript poems were found, along with the sonnet by William Aytoun, her letters from Rome in 1848 and memoirs of Marcelly Graham and Elizabeth Barrett Browning — Collingridge was Eliza’s grandson.

The finishing touch is a photograph of Lady Pentland, the Governor’s wife, flanked by two turbaned sepoys wearing cavalry boots in the uniform of a regiment of Madras Lancers. The model soldier is a diminutive stereotype that appears in a number of the photographs taken on this day in 1918 at Governor’s House, including one of a chess set of sepoy figures in the main reception room. This is all fitting neatly into a pattern of Edwardian techno-orientalism, with a fusion of Mughal and English pomp going hand in hand with the aura of technocratic efficiency, yet neither omnipotent nor immovable, and vulnerable to both popular opposition and raw nature.

Lady Pentland recalls, in her memoir of her husband, that on Sunday 10th November 1918, the doors of Governor’s House had to be shut against a hurricane, which at night rose to a cyclone. “It seemed as if the powers of darkness had burst out in a last desperate fury. The thunder was drowned by the roaring wind and slashing rain; the house shook; the floors were a sea. In the morning great trees had fallen about the compound and blocked all the roads; wires lay in a tangled jumble on the ground, and lights, fans, telegraphs, telephones and trams were useless.”

The storm delayed the news of the end of the war from reaching Madras for 36 hours. It wasn’t until the afternoon of the 12th that Pentland received the much anticipated message ‘Armistice signed’. Collingridge was despatched immediately to consult with the Chairman of the Publicity Board, “and in an hour or two posters in three languages were up on the walls and being hurried round the streets fixed to jutkas and bicycles.”4 The war was over: perhaps the trouble would cease.

It didn’t of course, and there is a brief post-script that points to the vital uses of instantaneous persuasion across continents to which the telegraph was put, although not always to the desired effect.

In August 1917, the Government of Madras were startled by a momentous telegram from Simla (the Summer residency of Indian Government) saying that “in two days, on 20th August, the Secretary of State would announce in the House of Commons that H.M.’s Government had decided to take steps in the direction of responsible government for India as soon as possible” — and so offering a diluted form of Home Rule. And then a second telegram “proposed that an amnesty should be granted to all those offenders who had been dealt with on political grounds.” To Pentland’s consternation, this meant the release of Mrs Annie Besant, the British theosophist and campaigner for Indian self-determination. She was based in Adyar, in Madras, and a particular thorn in Pentland’s side. Not only did she support Home Rule, but also womens’ rights, worker’s rights and (worse!) had the power of a newspaper that she edited, New India, behind her. In June 1917 Besant was interred in the hill town of Ootacamund by Madras Presidency police, and became the focus of a campaign by the Congress Party for her release.

Lady Pentland reports: “The Madras Government unanimously agreed that both announcement and amnesty were inopportune and unwise; and Pentland telegraphed on his own behalf to the Secretary of State and to the Prime Minister, Mr. Lloyd George, urging postponement and further consideration of steps so momentous and irrevocable.”

The telegraph flashed to London at the speed of light, but to no avail.

“The announcement was made, full liberty was restored to Mrs. Besant, the Secretary of State and the Viceroy made a tour of India in the cold weather of 1917-18. In 1918 their Joint Report was published, and in 1919 the scheme passed into law as the Government of India Act.”5

This Act was a baby carrot accompanying a very big stick: the Rowlatt Act, which led to the Massacre of Jallianwala Bagh in 1919, and demonstrated that the hawks were still in charge. Independence was inevitable, but the British would not let go without thirty years of struggle by the nationalist movement, the rupture of a second world war and the catastrophe of partition.

© William Owen 2026 - All rights reserved

For more on Government House …

Lady Pentland: The Right Honourable John Sinclair, Lord Pentland G.C.S.I, a Memoir, London 1928

Madras Mail, quoted in Arnold: Looting, Grain Riots and Government Policy in South India 1918, Past & Present, No. 84 (Aug., 1979),

The Mail and the Times merged in 1921, providing another date bracket.

Pentland

Pentland