14. Loot and arson - the destruction of the Yuanmingyuan

After the Great Uprising came the 2nd Opium War. Eliza's brother embarked for China with his regiment, part of the British & French force that destroyed the vast cultural complex of the Qing emperors.

In India the Great Uprising continued throughout 1858 and ‘59 and for years afterwards as a guerilla war in the hills that stretched across the border into Nepal. The scale of the threat to British rule is encapsulated in the sentence: ‘Of the 139,000 sepoys of the Bengal army, all but 7,796 turned against the British.’1

The sepoys of Alfred Abercromby Dick’s regiment rebelled at Jabalpur on 1 July 1857, two months after the rising at Meerut in which his cousin John MacNabb was killed. They seized the regimental colours and so the 52nd Native Infantry became a non-regiment as far as the British were concerned, decommissioned. Alfred escaped and fought across the Gangetic plain, serving in one of the British ‘moveable columns’ that used mobility and terror to compensate for lack of numbers.2 Eliza’s youngest brother then found a permanent home with the First Sikh Cavalry, later known as Probyn’s Horse; this was a regiment of Lancers founded at Lucknow to put down the uprising and commanded by his friend, Dighton MacNaghten Probyn. Alfred was Adjutant and second in command and in 1871 succeeded as Commander.

Probyn’s Horse was an ‘irregular’ regiment with a fearsome reputation. The European officers affected Indian dress. They wore khaki cholas and fetching pale-blue plaid turbans: ‘Each man is armed with a tulwa [sabre] and brace of pistols, and one or two troops with lances. To command a regiment of these semi-barbarous troopers requires no small ability, tact, and personal courage, as well as knowledge of the native character, and both Probyn and Hodson [of Hodson’s Horse] are beloved by their wild horsemen’. This was the recollection of Sir Edmund Verney, a naval officer who was at Lucknow with Probyn; his use of the term semi-barbarous is interesting — he was of course referring to the Sikh troopers and non-commissioned officers — and, in the light of the outcome of this story, it may offer us something to reflect on.

In the National Army Museum there is a print of an artfully composed group photograph of the commissioned and non-commissioned officers of Probyn’s Horse, taken in Peshawar in 1862. Picture an orientalist fantasy animated by the threat of extreme violence. The commander, Dighton Probyn, is at the centre on a low seat, holding a tulwa in his right hand by the scabbard, not the hilt; he is looking at what might be a document held in his left hand and ignoring the camera. Some of the officers — the Europeans a little awkward and lumpen — gaze at Probyn; the sikhs face the camera, confident and strikingly handsome. Alfred Dick lounges on the floor, his head almost in Probyn’s lap, relaxed but supine, lost in thought. The lounging foreground soldier is a common motif in military portraits of the time but for a group to appear this casual takes considerable care. On horseback, their kit included leopard-skin saddle pads and, after 1864, a fetching cummerbund of red Kashmir wool with gold lace and patterned ends. This was high camp with an air of menace — albeit genuine, not mere theatre.

The British officers of cavalry regiments of the Indian army commonly wore European uniforms (as did certain irregular regiments, including Hodson’s and Fane’s Horse). By ‘going native’ the officers of Probyn’s Horse may have recognised two essential facts: first, that the remaining trained cavalrymen of the Sikh Khalsa army were essential to any British victory over the Indian uprising (“When the Mutiny broke out in May, 1857, the first need of the Government was for troops”3); and secondly that the catalyst for the rebellion had been contempt for Indian national rights, religions and customs displayed by a succession of evangelical ‘reformist’ Governors General. Whatever the motivation, Probyn’s Horse festishised a style of brigandage reminiscent of Byron in Albanian costume in his portrait by Thomas Phillips, and this they combined with bravura military action and distaste for the regularity of regimental dress. Their discipline was of a harder kind: the commander imposed a fine of 4 annas per day for 15 days on any soldier guilty of neglecting his horse; other regiments regarded this as harsh.

Probyn’s Horse took a prominent role in breaking the siege of Lucknow and in suppressing the uprisings across Avadh in the hot-weather campaigns in 1858. Alfred Dick had a reputation for bravery: “On one occasion he charged single-handed through a body of mutineers and was wounded, turned and charged them again, and was wounded a second time.”4 The Lancer’s last action in the uprising was at the fort of Bungaon, a short march from Gonda, which cleared the last of the rebels from Awadh but left 50,000 (no less) who had escaped into Nepal and continued to threaten the British for many months. This was in May 1859, so when a history gives the dates of the rebellion as 1857-58, don’t believe it.5 At Bungaon Alfred Dick was surrounded by rebels and very nearly killed, his life saved by Sowar Dyal Singh, who was awarded the Order of Merit, the highest award available to an Indian officer. Even the medal system had its own little apartheid. At Lucknow, Dighton Probyn was recipient of one of the shower of Victoria Crosses (182 of them) awarded to British officers — and only British officers — in the First War of Independence, to show how their bravery had compensated for the national humiliation occasioned by ‘the Mutiny’.

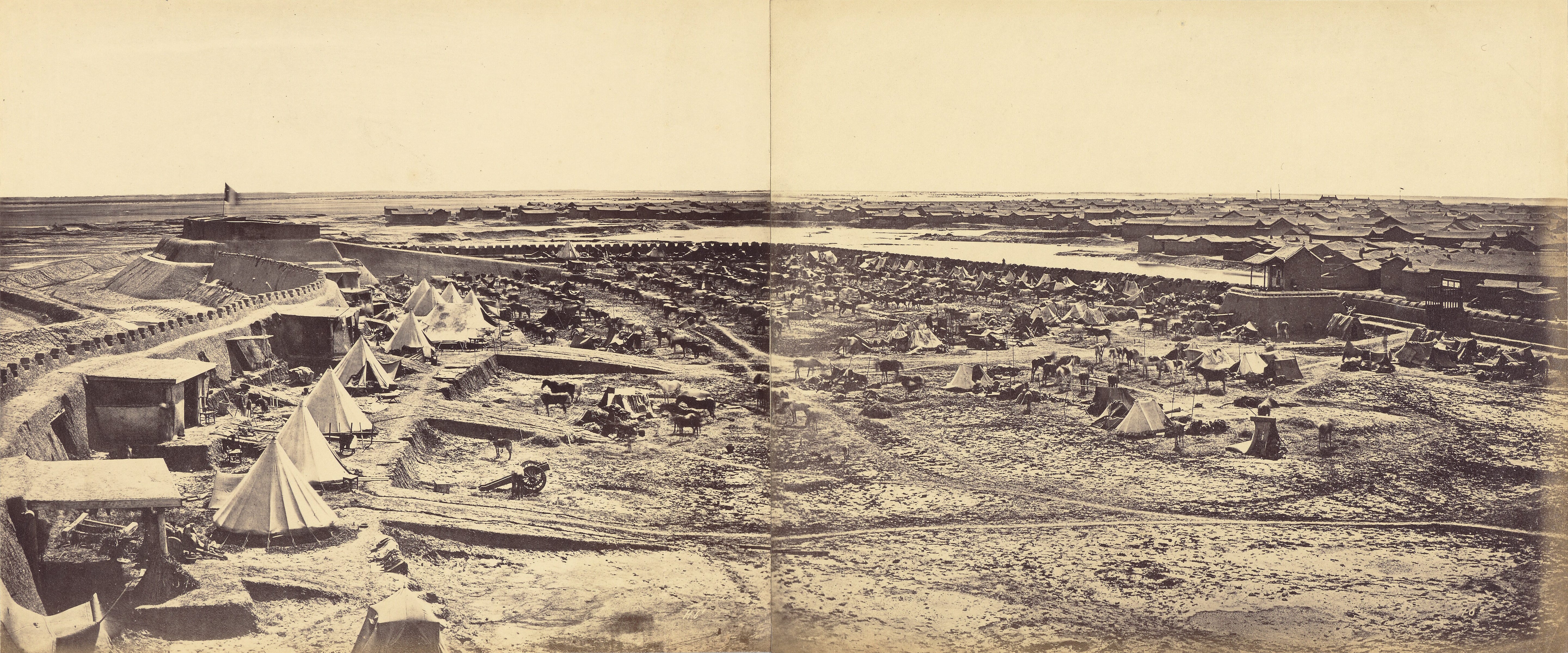

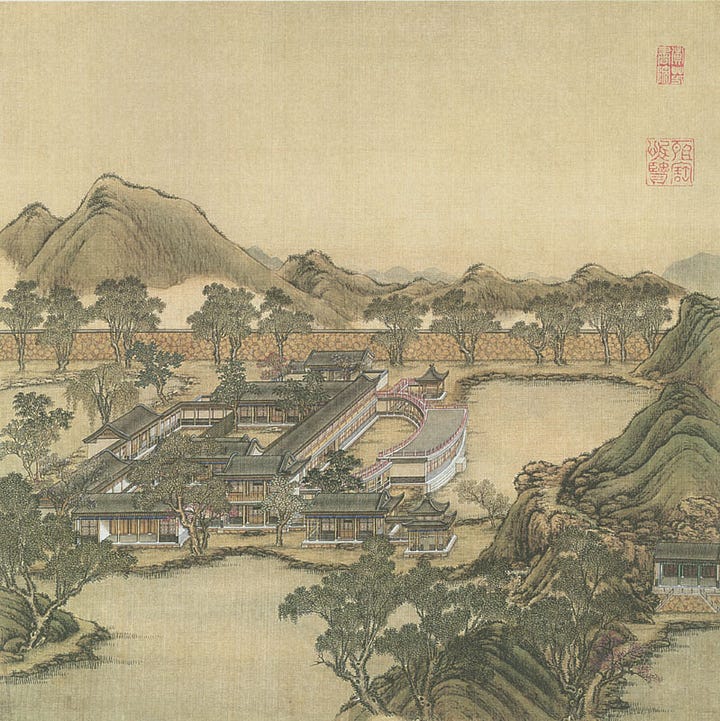

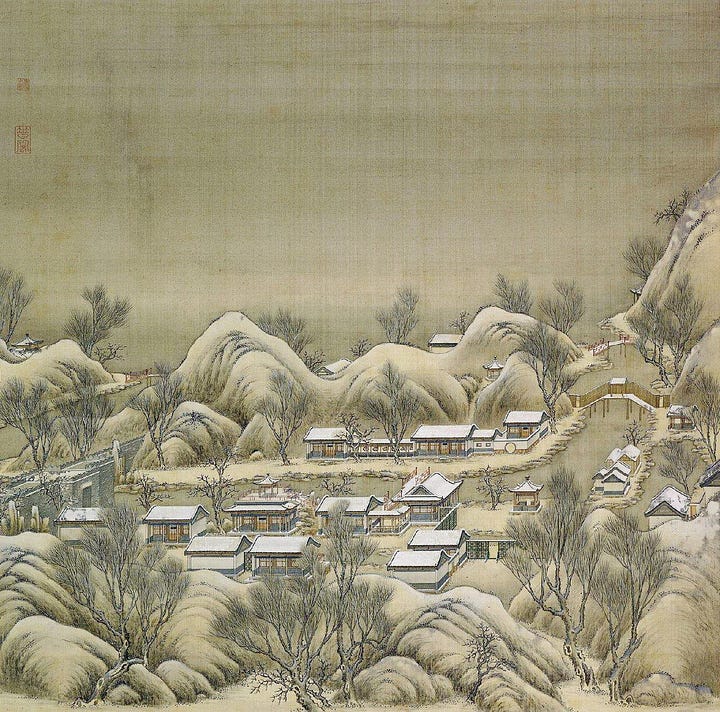

More medals were won when the regiment shipped out for China in 1860, as part of a combined British and French invasion force that fought its way from the coast at the mouth of the Pei-ho river to the gates of Pekin (Beijing), an ‘expedition’ that came to be known as the Second Opium War. As in the First Opium War, 21 years earlier, the primary aim was financial gain: specifically, to enforce the legalisation of opium exports and extract trading rights and diplomatic privileges from the Qing emperor. Probyn’s Horse took part in the capture of the Taku and Pehtang forts and the surrender of the Chinese capital that culminated in the looting by British and French troops of the Yuanmingyuan, the Garden of Perfect Clarity — also translated as Garden of Perfect Brightness, or of Pure Light. This was a complex of many dozens of palaces, gardens, libraries, pavilions, temples and schools both religious and secular; more than 650 individual structures, arranged in the landscape in 150 formal views over an area of 3.5 square kilometers. In British and French reports this was described diminutively as ‘The old summer palace’, as if a single building of little note. Think of Versailles, add in Fontainbleu, Blenheim and Sans Souci, perhaps the Palais du Louvre and the Uffizi and Hermitage as well, then the various Papal libraries in Rome and the Bodleian too, and you have some idea of the regal magnificence and cultural significance of the place. Yuanmingyuan was the crowning glory of Chinese civilisation, “a vast and sumptuous repository of the greatest productions of the country’s royal culture, including architecture, gardens, painting, sculpture, and especially decorative arts”6. The British burnt it to the ground.

Ostensibly, the total destruction was a reprisal for the capture at Tangchow of a small party of soldiers involved in a parlay with the Chinese. These were in the main officers of the two cavalry regiments, Fane’s and Probyn’s Horse and, fatefully, they were accompanied by a correspondent of The Times named Thomas Bowlby who had captured the affections of the British High Commissioner, Lord Elgin (it wasn’t he who ripped out the Parthenon frieze — that was his father). Elgin, the 8th Earl, had expected his relationship with Bowlby to result in favourable column inches in The Times; he was, for Elgin, ‘the means of diffusing sound information on many points’. Elgin’s hopes were dashed when Bowlby was tortured and died in the gaol in Tongzhou to which the prisoners had been despatched, and there he wrote the last entry in his diary in a book rediscovered in 2015; it made grim reading.

Had Bowlby survived he might have reported the atrocities he saw. “He writes of innocent civilians bayonetted to death by French troops and of Chinese people blown apart by British field guns” leaving “perfectly awful wounds”.7 This was Britain’s new weapon of mass destruction, the Armstrong breech loading field gun. Just as steam-powered gunboats had given the British Navy a technical advantage in the First Opium War in 1839-40, the Armstrong gun gave its armies a decisive edge over the Chinese in the Second Opium War. The Armstrong’s breech loading mechanism enabled a high rate of fire, and its compressed steel construction and rifling gave it tremendous range and accuracy, inflicting those “perfectly awful” wounds on the Tartar gunners at their emplacements in the forts.

Bowlby wrote: “It smashes whatever it comes in contact with, such a thing as a flesh wound being quite impossible. Going round the walls I passed a mass of Chinamen drowned in the ditch in their frantic efforts to escape — one poor fellow was moored by his feet in the mud — the water rose with the tide first above his mouth and there he stood drowned”.

Other witnesses reported similar effects. The translator Robert Swinhoe, after the British attack on the Chinese fort at Pehtang, wrote:

“Numbers of dead Chinese lay about the guns, some most fearfully lacerated. The wall afforded very little protection to the Tartar gunners, and it was astonishing how they managed to stand so long against the destructive fire that our Armstrongs poured on them; but I observed, in more instances than one, that the unfortunate creatures had been tied to the guns by the legs” [4]

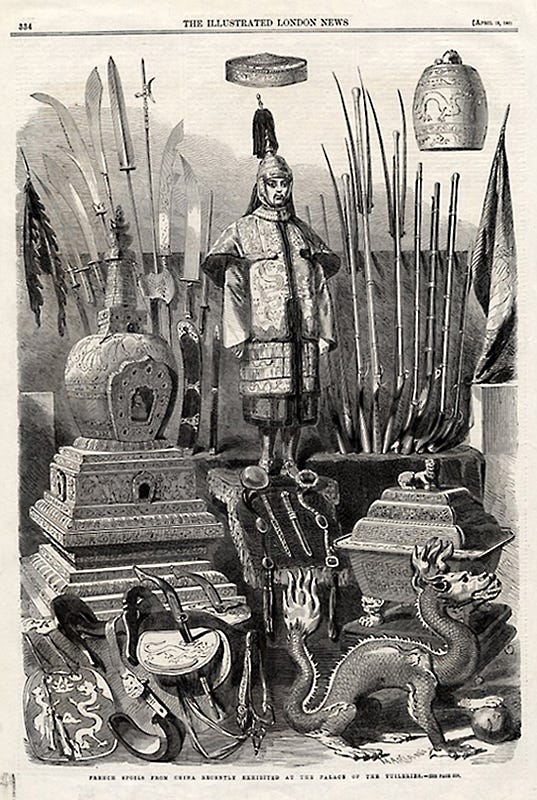

The carnage was recorded by Felice Beato, a pioneer photo-journalist who photographed the gruesome aftermath of the battle and the many Chinese corpses at the ramparts of the Taku forts. This was one of the earliest wars to have been photographed (the Mexican-American war was the first, in 1847, then Crimea, then the Great Rebellion) but the effect on the French and British public would have been lessened by the inability of magazines and newspapers to print photographs; that had to wait until the 1890s and the invention of halftone lithography. Instead, photographs were redrawn by engravers onto woodblocks or etching plates for publication in illustrated weeklies, such as the Illustrated London News. These images were usually faithful copies, but indistinguishable from war artists’ drawings and lacking the tonal range, detail and authenticity of the photographic image. The immediacy and sense of ‘being there’ inherent in photographs was lost in translation to the printed page. Unsurprisingly, exhibitions of photographic prints of the battles drew huge crowds, but only after the images had made a long sea voyage by steamer.

The taking of the forts on the coast in mid-August preceded a two month march on Tangchow, 10 miles short of Pekin, where a numerically superior force of the Chinese army was defeated. The Europeans then moved on to the capital and on the 6th October the French, virtually unopposed, took the Yuanmingyuan complex which lay about 5 miles North West of the city walls. Then the looting of the palaces and libraries began.

Swinhoe writes of looting by the French — “they are cursed with a mania for destruction” — and notes: “I am sorry to say that this mania for loot has taken complete possession of the [British] navy - officers & men - few commanders try to check it.” The looting was, nonetheless, arranged by prior agreement between the commanders of the British and French armies.8

A highly refined description of what happened next can be found in the official regimental history of the 11th Bengal Lancers, as Probyn’s Horse came to be known in 1862. ‘Unwilling to expose his force to the demoralization of indiscriminate looting, Sir Hope Grant confined his men to camp and appointed officers to collect as far as possible what belonged to the British army.’(!)9 Other sources say, with greater candour: ‘the British officers rounded up all of the loot they could, and sold it back to the men at a two-day auction.’10

The ‘official’ haul of loot according to the Lancers’ regimental history amounted to £26,000 - a number that bears no relation even in mid-19th Century terms to the true value to the Chinese people of what was pillaged, and possibly refers only to a stash of gold discovered and distributed amongst the 10,000 soldiers. The resulting prize money was £4 per soldier (about £3500 in equivalent income today) but many from Probyn’s Horse ‘took away pony-loads of immensely valuable silks and satins’.11 Their commander joined the looters too, but on behalf of his Queen, an act blessed with moral justification by the Reverend MacGhee, an army chaplain distinguished by his racism and admiration for British audacity. MacGhee recalled that Dighton MacNaghton Probyn extracted two ‘enormous and splendid enamelled bowls, which the army has presented to Her Most Gracious Majesty [Victoria], at Major Probyn’s request, who took them from the hall himself – minor spirits, being deterred from touching them by their vastness, were contented with some smaller and more suitable memento. But a difficulty is a just thing for Probyn; he contrived to get them away when no one else thought of attempting it.’12 This was according to MacGhee a laudable action of no consequence to the Chinese: “John Chinaman is not at all of a religious turn of mind, he very seldom goes to ‘Chin-chin,’ or pays his respects to his peculiar divinity … We have constantly occupied their temples, and they never seem to care much about it”.

The Chinese Government estimates the losses to be millions of individual works of art, yet many of these survive today in European museums and private collections: Chen Mingjie, director of Yuanmingyuan, has said: “Based on our rough calculations, about 1.5 million relics are housed in more than 2,000 museums in 47 countries.” Chinese researchers are scouring the world’s museums for evidence.13

The totality of the looting is evident in the British Museum collection which includes two bronze doorplates carefully unscrewed from the doors they protected from fingermarks, a fine architectural detail picked apart from the building they adorned with great care by a British soldier. The V&A has a manuscript looted from Yuanmingyuan with hundreds of sheets of silk containing “The Illustrated Regulations for Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Present Dynasty”, painted with extraordinary precision in brilliant colour by the artist Lang Jian. Other collections include much of the actual paraphernalia itself: imperial thrones, robes, seals, flags, caps, umbrellas and sceptres “in pure gold with stones of jade”; thousands of unique works of art and literature; silk, pearls, gold, ivory or jade, bronze sensers and animal heads; furs, watches, clocks; military standards prized by the British as spoils of war to place in their regimental chapels; perfectly shaped jade objects of rare sizes; laquerware and works of cloisonné ‘surpassing all previously known dimensions’; ceramics of all shapes and composition and from all periods. They can be found at the British Museum (where the ceramics are thought to be the foundation of the British Museum’s vast collection of Chinese porcelain), the V&A, the Royal Collection and Wallace Collection, amongst many private collections and provincial museums.

British witnesses to the destruction remembered the gardens, not the architecture, which were reminiscent of the English landscape gardens of William Kent, Capability Brown and Humphry Repton. This would have been less of a surprise to English observers had they understood that Kent and Brown had borrowed from the Chinese appreciation of irregularity and naturalism in garden design which had first reached England in the late 17th Century, via Dutch traders and English diplomats in Holland; this later came to be known as the Picturesque, a word overused by Swinhoe in his descriptions of the gardens; it was a style much appreciated by the Directors of the East India Company, some of whom would have been familiar with the villa gardens on the islands facing Canton, and who commissioned Repton in 1806 to design the gardens for its college at Haileybury. There was nonetheless a European quality to parts of the Yuanmingyuan, the source of which was the Jesuit mission serving at the Qing court.14 European-style buildings and fountains with clever hydraulics were designed for Yuanmingyuan by the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione between 1747 and 1766, to impress the emperor of the qualities of European design — and thereby of Catholicism as the origin of European genius. The cultural interchange continued. A second wave of enthusiasm for Chinoiserie was stimulated by the loot from China, and also a first wave of Japonisme, as there were many presents from the Japanese emperor to his counterpart in China decorating the palaces of the Yuanmingyuan, and these had found their way to France in advance of the wave of exports stimulated by the Meiji revolution.

French witnesses, in contrast to the British, focused more on the palace’s art and treasure. General de Montauban, who spent three days examining the contents of the palaces and libraries, wrote to the French Minister of War on October 8 that “nothing in our Europe can give an idea of comparable luxury.” He continued:

“It would be impossible, Monsieur le Maréchal, for me to convey to you the magnificence of the many buildings … which are known as the emperor’s summer palace; a succession of pagodas all contain gods of gigantic size in gold and silver or in bronze. Thus one single bronze god, a Buddha, is about 70 feet high, and all the rest is of a piece; gardens, lakes, and curious objects piled up for centuries in white marble buildings, covered with dazzling shiny tiles of every color; add to that views of a beautiful countryside and Your Excellence will have but a feeble idea of what we have seen.15

In France, the destination for the lion’s share of luxury goods was the court of Louis Napoleon. Eugénie, his wife, established a small museum inside the private family wing of the Château of Fontainebleau. The “Musée chinois” is still there today, available for public viewing. As far as the French were concerned, these objects were a source of imperial authority to be appropriated to garland the throne of Louis Napoleon and sanction the depredations of his armies in Indochina, North Africa and Guiana. For the British the gains expected were primarily financial and so in tune with their war aims. However at auctions in London and Paris after 1861 neither French nor British looters made quite the fortunes they expected, having created a massive oversupply of chinoiserie, their plunder reduced to ‘a bric-a-brac’.

Captain John Hart Dunne of the 99th Foot complained that looting ‘brings out all the worst passions of one’s nature’ and is anything but an amusing occupation for those without expertise or focus: ‘… the man who "loots" well must have a good knowledge of minerals and metals, & quick eye, a cool head, and, above all, a determined fixedness of purpose. He who hesitates is lost’.

Two such experts were James Bruce the Earl of Elgin and Captain Jean-Louis de Negroni, each of whom made substantial personal collections ‘for patriotic reasons’ and then, as a matter of either public generosity or carefully designed pre-marketing in a prestigious institution, arranged public exhibitions before consigning to auction: Elgin showed 11 out of 86 lots at the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) in 1862; Negroni displayed 484 objects at the Crystal Palace at Sydenham in 1865, which the Illustrated London News described as ‘worth over £300,000’. This brings to mind Victor Hugo’s verdict on the sacking of Yuanmingyuan: ‘Two robbers breaking into a museum, devastating, looting and burning, leaving laughing hand-in-hand with their bags full of treasures; one of the robbers is called France and the other Britain.’

One of the most important items taken from Yuanmingyuan and still surviving in the Biliothèque National de France, is an album of 40 scenes of the gardens and palaces commissioned by the Emporer Qian Long from two court artists, Shen Yuan and Tangdai, and a calligrapher, Wang Youdun. The album’s end papers are foxed but the illustrations appear to be in good condition, and can be seen in high resolution at the BNF’s Gallica digital catalogue. Here are painted views of the Library of Collected Fragrances, the Library of the Four Seasons and the many halls of Diligent and Talented Government; the Universal Peace Building, in the shape of a buddhist swastika; the Jade Terrace of Paradise Island; the Deep Vault of Heaven — also known as the Prince’s School; the Hall of Rectitude and the Green Wutong Tree Academy, amongst many others. The documents are so important because they record faithfully the landscape and structures that were lost when, on 18 October 1860 after 10 days of pillage, James Bruce the 8th Earl of Elgin ordered the entire Yuanmingyuan to be burnt to the ground.

Probyn’s Horse was in the detail that carried out the work of destruction. Firing so many buildings dispersed over an area of 860 acres took 4000 men three days. When the work was complete the Yuanmingyuan was reduced to ashes, along with any objects not yet looted including thousands of rare books in the libraries, their script incomprehensible to the European barbarian-soldiers. Even Elgin recognised: ‘Plundering and devastating a place like this is bad enough but what is worst is the waste and breakage’. His justification was peevish and infantile: ‘It was the Emperor’s favourite residence, and its destruction could not fail to be a blow to his pride as well as his feelings.’ So said a man scorned, his ticket to glory snatched from him by the death of the journalist from The Times.

Elgin died in 1863 and his ‘collection’, some of which had already appeared in public at the South Kensington Museum, was put on sale at Christie’s in May 1864. At least one press report, in the Leeds Times, displayed a sense of awkwardness, if not remorse, about the moral consequences for the nation.

“Nationally, we pretended to be proud of it at the time, but in a very short space people grew rather ashamed of the transaction, and such officers as brought home with them portions of the plunder were glad enough to convert their booty into cash through the medium of the sale-rooms, pocket the money, and say no more about it. So great, indeed, was the scandal caused by the sale in Paris of some of the plunder brought home by the French that few people, having anything like a sense of delicacy, would like to have it known that they possessed anything in their drawing rooms which had once formed part of the furniture of the great palace. Within the last week, however, London has witnessed a sale which has revived this awkward business upon the public memory”16.

Today, the Yuanmingyuan has been wiped not only from the face of the earth, but also from British text books and memory, recalled only occasionally when an artefact appears in a metropolitan or provincial sale, often attracting huge prices, sometimes from Chinese benefactors determined to restore the works to the nation.17 At these moments Lord Elgin, like his father, becomes a figure of national division.

After the war, opium sales from India to China boomed, rising from £6.1m in 1859 to £9.2m in 1878 — today this would be at least £20bn a year in terms of relative economic share. Opium sales provided the British Crown with between 15-20% of its entire revenues from India in the 20 years from 1860 to 1880. In volume terms the quantity of opium sold from British ships into Chinese and other SE Asian ports increased from 4000 to 6500 metric tons, creating a hugely damaging burden to the Chinese people and the Chinese economy.18

For the 11th Bengal Lancers there was period of relative quiet, interrupted by a Hindustani rebellion in Umbeyla in 1864. The need to keep the sowars trained and fit between the inevitable periods of unrest encouraged the early adoption of polo by the regiment, and so to the introduction of an ancient Afghan sport to a wafer-thin layer of British society. Dighton Probyn departed in 1866 to became something of a talisman of the British empire, as the good-looking and heroic equerry to the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) and then devoted servant of Queen Alexandra and resident at Sandringham. He was witness to Alfred’s marriage to Fanny Macnaghten at St George’s, Hanover Square, in 1867: she was a cousin of Probyn’s and the daughter of Elliot Macnaghten, a former chairman of the East India Company and at the time of the marriage still a member of the powerful India Council and a close friend of Alfred’s father, Abercromby Dick.

Alfred led his regiment from 1872 until his death in 1874, aged 40 (he had received two serious wounds during the great uprising). He, James Dick and John MacNabb were the family’s casualties of the imperial wars. Robert Hunter too: he died in Crimea. The other brothers, cousins, and uncles survived and prospered, and Eliza continued her resolute defence of the family but not always the British state and its government, calling out hypocrisy and malfeasance whenever the occasion demanded, and often in verse.

© William Owen 2025 - All rights reserved

Dalrymple, William: Delhi, 1857: a bloody warning to today's imperial occupiers, Guardian 10 May 2007

Alfred’s activities in Great Uprising: Capt. B.S.C. ; 2nd Lt. 1855 ; Lt. 1857 ; Capt. 1867 ; served with Kamptee Movable Col. in Saugor and Nerbudda territories from Aug. 1857 to Feb. 1858 ; present at actions of Kutungee and Moorwarra ; served with Saugor F. Div. from Feb. 1858 to Feb. 1859 ; present at battle of Banda, capture of Kirwee*, and action at Sahao [Uttar Pradesh ](severely wounded) ; served in Trans-Gogra dist. of Oude throughout hot - weather campaign of 1859, present at action of Koolee-ka-Bund and capture of fort of Bungaon (desp., medal with clasp) ; served throughout campaign of 1860 in China, including action of Sinho, capture of Taku Forts, actions of Chaukenwhau and Palichau, and surrender of Pekin (medal with two clasps) ; d. 1874. *Kirwee: Forty-two lacs of rupees in coin, with an enormous quantity of gold and silver utensils and jewels, were captured. Edinburgh Academy Register 1824 - 1914.

A History of The XI King Edward’s Own Lancers (Probyn’s Horse), Capt. E. L. Maxwell 1914

Maxwell

The confusion derives from the Indian Mutiny Medal which is dated 1857-58, the latter year being the date when the medal was approved and cast, not the date of the end of the war.

Thomas, G.M.: The Looting of Yuanming and the Translation of Chinese Art in Europe, 19th C Art Worldwide, Volume 7, Issue 2, Autumn 2008

The Times, Friday July 12 2019

The New Army List, 1873, p. 379a

Maxwell

Hill, Katrina: Journal of the History of Collections, Vol 25, No 2, July 2013, pp 227–252,: ref. G. J. Wolseley, Narrative of the War with China in 1860 (London, 1862), p. 241.

Maxwell. £26,0000 is £3m to £32m depending on whether measured in terms of prices or incomes, both fairly meaningless figures given the circumstances which would necessitate massive undervaluation caused by ignorance of true value and difficulty of haulage back to India, then London. The £4 prize money given to each soldier would be worth around £3500 in income terms.

Hill. McGhee wrote: ‘We have constantly occupied their temples, and they never seem to care much about it, and only in some cases took the trouble to remove their deities; not that we generally disturbed their very ugly images, although I have seen a statue of Confucius at Canton forced to smoke a very short clay pipe.”

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2009-10/19/content_8809705.htm

https://www.creighton.edu/sites/default/files/2022-01/30-Jesuit-Gardens-China.pdf

Thomas: A translation is given in Letter of October 12 and 15, 1860, in de Mutrecy, Journal, 374–78 at 377.

21 May 1864, quoted in https://www.fokum-jams.org/index.php/jams/article/view/63/117

An archaic bronze water vessel taken by a British soldier from the Yuanmingyuan was sold in the UK in 2018 to an anonymous buyer for £410,000, despite calls for a boycott of the sale from the Chinese State Administration of Cultural Heritage

See Richards, Betteridge, Rowntree, Hansard