1. Life and death across the great world belt

Duine-uasals in the Highland margins uprooted to India and separated from family, with a precarious opportunity to make their fortune.

Eliza Ann Harris Ogilvy, née Dick, was born into an East India Company family, so no ordinary family. There were Scottish and English branches. The Scots — the Dick family of Atholl — owed their position to the patronage of Henry Dundas, William Pitt’s political fixer in Scotland, who dispensed East India covenants in return for loyalty to the government in London. The English family, the Wintles of Southwark, saw their prospects transform when Eliza’s great aunt, Jane Wintle, was introduced to William Devaynes: he was MP for a rotten borough and five-times Chairman of the East India Company, a wealthy banker, government contractor, West Africa trader and serial placemonger; she became his concubine and later wife. From this beginning in the late Eighteenth Century and over 150 years, through six generations and across half the world, the Dicks and the Wintles guarded the benefits of patronage closely, building an extended network of family and professional relationships that granted access to position and generated wealth, influence and prestige.

This meant that everyone in the family, male or female, worked for the Company in some capacity or other. Eliza’s maternal and paternal grandfathers each climbed their way through the hierarchy of the Bengal civil service. Both men were well placed: hardly nabobs yet both made fortunes substantial enough to lift them into ‘the coach trade’, the top 0.01% or so who could afford to buy or lease a carriage and pay the keep of horses, grooms and drivers. Dr William Dick in Calcutta (Kolkata) started out a mere surgeon’s mate, keeping sailors alive in the filthy lower decks of an East Indiaman, The Queen, but after what he called two lucky operations he was promoted to assistant surgeon, then surgeon to the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Robert Abercromby (a fellow Scot) and life became easier. He supplemented his income by operating a ‘madhouse’ for European women in Calcutta, and earned enough he thought to retire in 1802. He built himself a country house at Tullymet, in Atholl, on the edge of the Grampian mountains, but his family was large and the bills were steep and his savings were not enough to live without working and so, in 1805, back he sailed to the East Indies. In the Indian Ocean en route for Java Dick suffered the indignity of attack by a well-armed French naval squadron, but luckily (or there might have been no story to tell) his ship, the Cumberland, escaped the 74-gun Marengo, flying the flag of the celebrated but ineffectual Rear-Admiral Charles-Alexandre Léon Durand de Linois. Some weeks later, with the Governor Phillip Dundas and his secretary Stamford Raffles, Dick arrived in Prince of Wales Island — today Penang — to establish hospitals in the new Presidency. Penang was then a fever-ridden military base on the Company’s vital trade route to Canton, across which exports of Bengal opium were shipped to be slipped though Chinese borders to finance a reciprocal trade in tea, another albeit milder narcotic to which the British nation had become addicted1.

In Penang, Dick was well compensated for the risks to life and limb his new post necessitated. He received the princely annual salary of 10,720 Spanish silver dollars, which in comparative income terms would be worth about £3.5m today. This was danger money, to compensate for the high mortality rate among those remaining on the island.

Dick survived, and remained only two years, returning from Penang to London in 1808. In the following year he acquired a lucrative position with his old employer, the East India Company, as chief examining surgeon at the Company’s headquarters in Leadenhall in the City of London. This was a post he held for nine years while running a private practice from Hertford Street, in Mayfair. Dick’s patients included artists and poets, men like Sir Walter Scott and Sir George Beaumont, the founder of the National Gallery, and the portraitists Martin Archer Shee and John Hoppner, illustrious members of the Royal Academy and their aristocratic patrons on whom Dick practiced his speciality of treating liver diseases with Calomel, a compound of mercury prescribed in small doses, frequently given, potentially lethal.2

James Wintle of Southwark, Eliza’s other grandfather, began his career as a cocky 16 year-old writer — a clerk or factor — as did the vast majority of EIC civil servants. A writership was so valuable a commodity it could be traded for a seat in Parliament, so it was said. For Wintle, it resulted in becoming a Calcutta appeal court judge and a man of surprising wealth, even by the standards of the so-called Honourable Company.

In his will, Wintle left the enormous sum of £63,000 in Bengal bonds along with a fashionable house in Lansdown Crescent in Bath and a coach and his chattels: in total, this would have a relative income value of around £88 million today, which he would have called his ‘competency’: sufficient wealth to live well without working for the rest of his natural life. In Calcutta James led an expensive life, and although as a senior Company judge he was well paid, this money came from trade, not savings. The word ‘opium’ is written by his name on a family tree dated 1906, when the recollection was still alive that a good part of the Wintle wealth came from speculation in opium exports to China as a private trade.

James’ wife, Sarah Jennings, was the daughter of an indigo planter of Jessore and is the subject of The Great Grandmother in Eliza’s anthology, Poems of Ten Years. She laboured too, and bore 16 children in 25 years, fully eight of whom died young. Three of Sarah’s children - Emily Augusta (7), Harriet (6) and William Devaynes Wintle (4) - were lost together on one terrible night in March 1809, drowned in a hurricane off Mauritius while returning home from Calcutta in an East Indiaman, the Lady Jane Dundas, one of four ships to be lost in the storm and which, with cosmic irony, was named for the wife of the Dick’s benefactor.3 Twelve hundred souls died that day. The children are memorialised in a gold ring with three crystal glass panels over a plaited lock of each child’s hair, each within a black stone border, and their names engraved on the outer rim4. Their loss is the subject of Eliza’s poem which begins with the premise - one which, in these circumstances, cannot be denied - that everyday experience beats tales of knights and maids for its power to generate pathos. Sarah Wintle, blind, looks out to the sea that took her children, as her surviving children’s children’s children play on the beach. This is a conscious acknowledgment of the costs of an inter-generational enterprise ‘across the great world-belt, whose folds enamelled // Work in and out among the isles’. Only eight of the sixteen Wintle children lived past youth, of whom three girls married Company civil servants and three boys joined the Company’s military or religious establishments: testimony to the near totality of family engagement in Company business.

This was the world into which Eliza was born in Bihar on 6th January 1822: tight-knit, well-rewarded, precarious. Her mother, Louisa, was Wintle’s eldest daughter: her father, Abercromby, was the fifth of Dr Dick’s six sons, every one of whom entered the Company service. Abercromby had one famously beautiful and spirited sister, Eliza Serena; she married George William Harris, who at the age of 17 was one of the breaching party that stormed the gates of Seringapatam in the siege that ended Tipu Sultan’s resistance to the East India Company in Mysore5. He was sent home in charge of the captured Mysorean and French standards, which he presented to George III. This was the last battle of a war waged and won against Tipu Sultan by George William’s father, General George Harris: he in turn was rewarded for his victory with a Barony and c. £143,000 in prize money, which he used to purchase Belmont, an estate in Kent complete with orangery, stables, and a grand house flanked by a pair of pepper-pot turrets. Eliza’s middle name honours a prestigious family union.

Eliza was baptised in Dinapore, near Patna, when 13 days old. She was born and lived the first year of her life in Muzzafarpur, now a city, then a small town in the district of Tirhut, where the Gangetic plain tilts up towards the Himalayas and the land was used for the cultivation of opium in the south, indigo in the north; these two colonial crops framed the complex politics of the district.

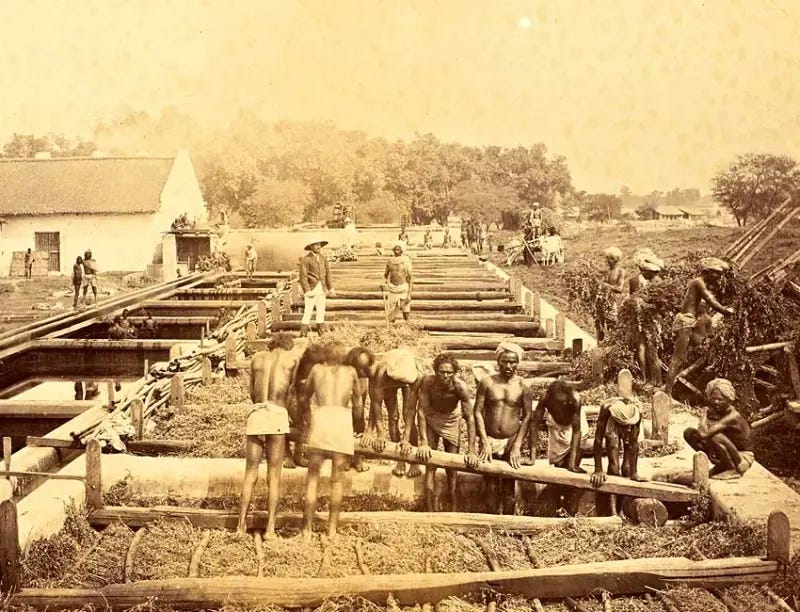

Both opium and indigo were grown under duress by the local raiyats — tenant farmers — who would have raised food for their families if they could, not cash crops, but they were coerced by debt deliberately fostered by loans advanced on the harvest. Debt was a whip wielded by the East India Company to force farmers into the production of opium, extracted from the seed pods of white poppies, manufactured under the Company’s monopoly and shipped out to China; or it was served out in contracts imposed by British ‘non-official’ indigo planters, whose factories processed the fibre of the deceptively pink-flowering plants into the blue dye concentrate they exported to the cotton mills of Britain, Europe and North America. Indigo was a material concentration of such a density of wealth that it was used as currency for repatriating profits from India and was the subject of much financial speculation: think of indigo as the Bitcoin of its age.

The administrative capital of Tirhut was Muzaffarpur, where Eliza’s father, Abercromby Dick, was the magistrate. He had an uneasy role. Tirhut was in the mofussil, up country, beyond the jurisdiction of the Presidency city of Calcutta. Different rules applied here and Dick had to work within a tangle of Moslem and Hindu law to keep the delicate balance between his employer, the East India Company (greedy for tax revenues), the Zamindars (landowners who collected taxes on the company’s behalf) the raiyats (their role was to be sucked dry) and the 200 or so indigo planters and their European employees who operated sizeable indigo factories and outworks in the district.

For the Company, the Europeans were a tolerable nuisance; in the 1820s its’ attitude to non-official ‘interlopers’ was unfriendly because its policy was to ally with the Zamindars who farmed the tax revenues. The indigo planters often brutally oppressed the raiyats and were encroaching in different and ingenious ways on the Zamindars’ rights; they were barred from owning land but worked around this prohibition by using their ‘native’ officials (amlahs), as proxies; or they contracted Zamindars to persuade their villagers to grow indigo. Wherever a Zamindar failed to meet a contract Abercromby Dick would have had to judge the inevitable suit between the local landowner and the plaintiff planter - they were aggressively litigious - or in other circumstances between the planter and amlah where the amlah had taken his signature on the deed too literally, and claimed the land for himself.6

This was the puzzle into which Abercromby Dick launched his career in 1818, at the age of just 24, after three years as an assistant magistrate learning the ropes. In Muzaffarpur, he would have had the company of his wife Louisa and his three daughters: Louisa, Charlotte and the infant Eliza; there would have been his colleagues in the Bengal civil service - the collector of taxes, the opium agent, the civil surgeon and an assistant magistrate or two - with whom to share a whisky in the evening, probably on the veranda of a bungalow in the civil lines, possibly with the officers of the local garrison too or the Anglican rector (the Dicks were Anglicans, lapsed Catholics), or a missionary in need of calming. The missionaries were a new and different form of nuisance; they had gained free access to India after the Charter Act of 1813, to spread often intolerant forms of christianity — perhaps there is no other kind — to muslims and hindus who were sensibly protective of their religious freedoms.

Occasionally Muzaffarpur would have burst into social life, especially at the end of the planters’ season in October. They were a rough lot, the ‘planters’ and a step down the social ladder from Company people. By nature and necessity these were risk-taking individuals gambling for high stakes in a hostile environment, albeit one of their own making. William Huggins, an indigo planter in Tirhut in 1824, described his peers, with vigorous enthusiasm, as ‘a hard working, healthy class of men, who inhabit one of the finest districts of Lower India, and are generally addicted to field sports and the pleasures of the table….These country gentlemen of India, during the cold season, hunt and give parties, at which mirth, plenty, and hospitality prevail; Bacchus is lord of the ascendant, and they indemnify themselves for the many dull, heavy days they have to pass during rain and manufacture’.7 Surviving an evening with these men would have taken fortitude. Facing them down in court in the interests of the Company (if not impartiality) would have taken backbone.

Indigo is not a tangent in the Dick family story but a central strand. Eliza’s youngest daughter, Violet, would marry an indigo planter in the Anglican Church in Muzaffapur, 40 years later: one of those ‘healthy class of men’, he was the great grandson of a liveryman coachmaker, one whom Eliza’s uncle, James Munro MacNabb, had patronised for purchase of a carriage in 1818, such was the social slippage of the age. Eliza’s mother Louisa was herself the grand-daughter of Ross Jennings of Midnapore, self-styled as ‘India’s first indigo planter’; and so Abercromby Dick was topped and tailed in blue.

In October 1823, when Eliza was 21 months old, Abercromby and Louisa returned ‘home’ to Scotland on furlough, after a stopover in Clifton, the Regency suburb of Bristol to which their Wintle grandparents had first retired, to baptise Eliza for a second time — was this ‘properly’? — alongside her new-born brother William.

The four children — Eliza, William and their elder sisters Louisa and Charlotte — were to be deposited with their uncle, Colonel Robert Dick, at the family home in Tullymet and there they would stay, as things transpired, for the rest of their childhood; it wasn’t until 1838 that Eliza and Charlotte returned to India to reacquaint themselves with long-absent parents and meet three siblings born in India since they had departed, 15 years before. Abercromby left his three year old daughter in June 1825 with a bible as a memento and guide, inscribing it to Eliza as: ‘a parting present from her fond papa … “Read, Mark, Learn and Inwardly Digest” Fear to offend. Love to please your Maker, Be Just, Be Merciful to your fellow creatures. Respect yourself.’ Family separation was a feature of East India Company life, part of a strategy for reducing child mortality but also one intended to preserve close cultural and family ties with England and Scotland, underlining the fact that India was an imperial exercise with never an intention to settle a colony, only to extract wealth and return ‘home’. This is one of the reasons why Company families exerted such a powerful influence on the development of British middle class culture: not only were they ambitious and super-connected but — so long as they stayed alive — they always came back.

The master of Tullymet, Colonel Robert Dick, was a war veteran, a dandy and a socialite, and after storied heroics in the Peninsular War and Waterloo was often absent suppressing nationalist dissent in Ireland - an irony forever lost on his republican niece Eliza. He was not the ideal guardian for three young girls but, fortunately for Abercromby and Louisa’s children, there were proxy mothers a-plenty including their dowager grandmother, Charlotte Dick (Dr William Dick had died in 1821) and her sister Mary MacNabb. The two sisters were the daughters of ‘Baron’ Alexander Maclaren of Maclaren. the clan chief, who had two uncles who had fought at Culloden. Mary was the widow of Dr James MacNabb of MacNabb: another with a claim as clan chief, another EIC surgeon too — he had practiced in Patna for most of his working life; and there was an aunt, Sarah Jennings’ younger sister Elizabeth Hunter, with a town house in New Town in Edinburgh and access to metropolitan society. These were the original strands of the Dick East India network: MacNabb of Arthurstone, Dick of Tullymet, MacLaren of East Haugh, Hunter of Thurston; they tightened when the MacNabbs’ daughter Elizabeth married her first cousin, the unmarriageable Colonel Robert Dick; she, along with Nancy Stewart, a second cousin and nanny to generations of stranded Dick children, completed the family at Tullymet.

Who were these people? Minor gentry, with many mouths to feed; ’duine-uasals’ in the Highland margins with feudal responsibility to raise men for the laird, which in the Dick’s case was the Dukes of Atholl, a dynasty at war with itself since the events of 17458. Like all Scots, they lived with the economic legacy of the Darien implosion of 1698-99; like all highlanders, after the disaster of Culloden they had diminished political power and social status; they were ex-Jacobites (in the main) who had been lucky enough to receive the call from the Company and, with it, an opportunity to make a small fortune and often a speedy conversion to an approved form of presbyterianism as part of the bargain.

The impoverished Edinburgh medical student William Dick, the first generation to be blessed by patronage, was the eldest of 20 siblings ‘without education or money’ to whom he remitted all his spare rupees to support. These were the Dicks of the lands around Tullymet: Balliekilvie, Convallach, Auchnagie and Drimmin. By the time of the second generation, the ties with them were being loosened by geographic and social distance, an emerging shift that created a lasting difference in class, and the Dicks who stayed came to be unkindly regarded by the Dicks who built the empire. In 1815, Eliza Serena Harris was driving four in hand — a luxury paid for by her husband’s generous allowance as a brigade commander — on a coaching tour of Flanders during the peace that preceded Napoleon’s escape from Elba. She wrote from Courtray to her brother William Fleming Dick in Bengal, expressing her regret at her father’s recent return to Tullymet from his private practice in Mayfair: “They are so surrounded by those queer relations, that I really feel ashamed that George [Harris, her husband] should ever see them…so vulgar as they are … I do not look to Tullymet for pleasure unalloyed”. “Remember” she cautioned her brother “that this is between ourselves.”9

Serena and Abercromby’s generation consolidated the gains of the first by pursuing social advancement through education, career promotion, making good marriages and the appropriate display of carriages, servants, silverware and portraiture. The Dick and MacNabb daughters were educated at schools in Perth or Edinburgh; the sons at Westminster School or Harrow and also, after 1824, at Edinburgh Academy, the school founded by Henry Cockburn and Leonard Horner to promote classical learning and teach Greek: Sir Walter Scott and Roger Aytoun — family connections — were founding directors. The boys would then go on to attend the East India Company college at Haileybury or the military academy at Woolwich. In India, at Fort William in Calcutta or Fort St George in Madras, they worked day-to-day and side-by-side with aristocratic English, Scots and Anglo-Irish statesmen: ‘Marquess Cornwallis, Lord Teignmouth, Sir Robert Abercromby and Sir Alfred Clarke … would readily vouch for’ William Dick MD.10 These senior nodes in the network influenced the development of new tastes and outlook, as did any number of energetic administrators, Scots and English, merchants and soldiers, often with little family money to fall back on but they were in India too so, like the Dicks and the Wintles, they were on the up. In the third generation - Eliza’s - the family became ever more heterogenous, with diverse Scots, English and Irish coming together in the close social and professional mix of Calcutta, a place so far removed from the social conformity of London that for gentry to marry trade was a commonplace and necessary practice, and one that accelerated social and geographical mobility. New families were added to the network through marriages made in Bengal, Bihar and Madras. There were the Scots: McLeod, Campbell, Low, Seton, Napier and Ogilvy; the Irish: MacNaghten; and the English: Harris, Shakespear, Thackeray, Millet, Prinsep and Tennant — all familiar East India Company names.

© William Owen 2024 - All rights reserved

Donald Maclaine, Java: Past and Present, Campbell, London, W. Heinemann, 1915. The silver dollars would have exchanged for around £2680 in 1805, equivalent to £231,400 in 2022 using RPI, but in relative income terms equivalent to £3m. The house might have cost some £5000, about two years’ pay.

Dick’s methods are described in his letters to Sir Walter Scott. As early as 1786 Dick contributed a paper to the influential Edinburgh journal, ‘Medical and Philosophical Commentaries’, entitled ‘Observations on Dropsies prevailing among the Troops in the East Indies’. Dropsy is a consequence of liver disease, one suffered by John Hoppner. See Mackillop, A: Human capital and empire, (n) p.189.

Eliza Ogilvy, ‘The Great Grandmother’, Poems of Ten Years, 1856. Sarah Jennings had 59 great grand children. Lady Jane Dundas was named for the wife of Henry Dundas, op cit. Total losses from the four ships sunk without trace that night were £368,611, according to a Parliamentary report which did not record the human fatalities (believed to be 1200 including 43 children and, on the Lady Jane Dundas, General McDowall, C-in-C Madras, Colonel Orr his wife and two children)

Composed of three graduated glazed hairwork panels, each within a faceted black stone border, to gold and monochrome enamel band with gilt inscription 'Emily Harriot & Willm. Wintle', the interior also inscribed 'Lost in the H C ship Lady Jane Dundas on their passage from Bengal to England, 1809', (one stone deficient), ring size Q. Sold for £562.50 inc. premium. Bonhams Oxford 7.1.2014

“A finer spirit never inhabited human form, and no human form was ever more lovely” (memorial in Tullymet cemetery). Eliza Serena died in 1817, probably in child birth in her fifth pregnancy. Her fourth, in October 1815, had resulted in complications and a still birth.

Colonising Plants in Bihar 1760-1950, Kerkhoff, Partridge, India 2014

Kerkhoff

Lord George Murray commanded the Pretender’s armies: his elder brother and half brother were loyal to the Hanovarians.

My emphasis. Eliza Serena Harris to William Fleming Dick, February 1815, from Courtray, Flanders. Harris family archive, Belmont, Kent.

Unpublished letter William Dick MD from Atholl to the Court of Directors of the United East India Company, 8 November 1802, requesting deferment of return to India ‘for reasons of extreme bad health’. This was an appeal to authority at the periphery that fell on deaf ears in the metropolis, and Dick’s request was denied.

There’s a lot to get one’s head around here. It’s fascinating.